National Park Rangers. These are the people on the front lines of our national parks. They’re the ones who protect our national treasures. They assist visitors, conduct educational activities, perform emergency medical services and protect our public lands from those who would abuse them.

In this article, we explore the history of the National Park Service Rangers, highlight the incredible work these women and men do, outline the unbelievable number of jobs they perform, risks they assume, long hours they work and share some of their amazing stories.

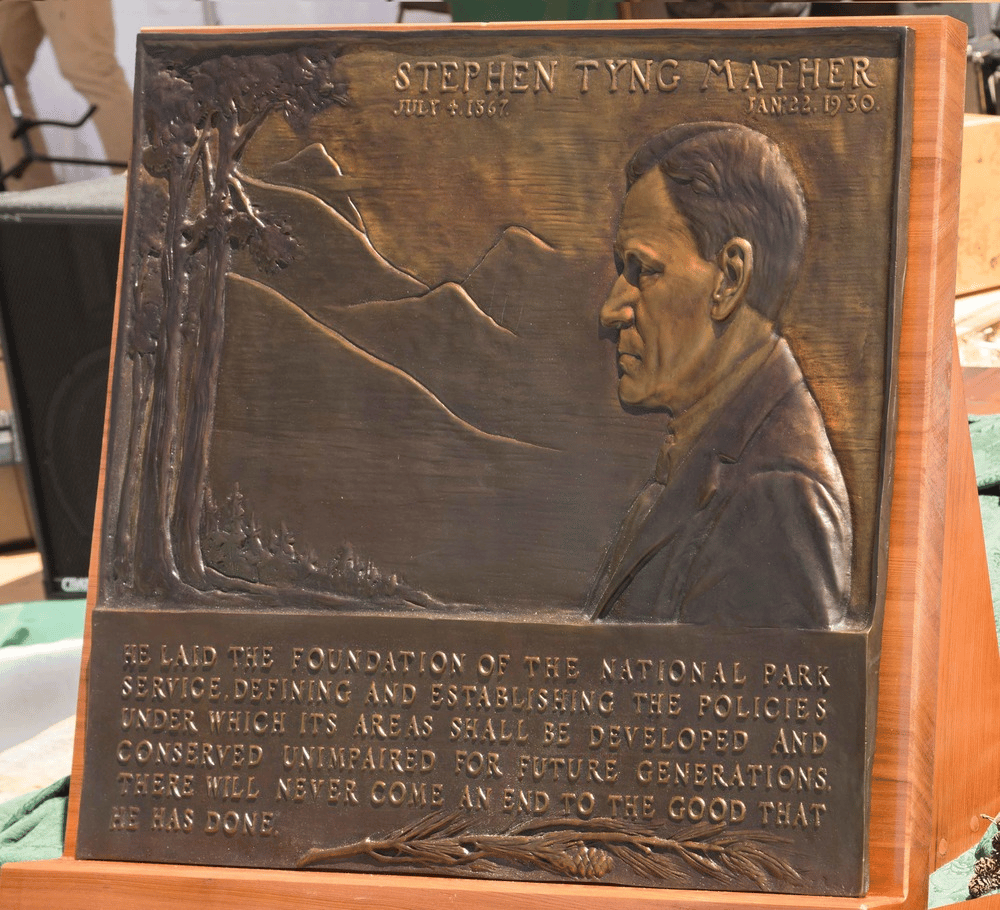

As the first Director of the National Park System, Stephen Mather, once said:

“The parks do not belong to one state or to one section…. The Yosemite, the Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon are national properties in which every citizen has a vested interest; they belong as much to the people of Massachusetts, of Michigan, of Florida, as they do to the people of California, of Wyoming, and of Arizona.”

Without the dedicated men and women who serve as national park rangers, however, it would not be possible to protect these important places and make them available to every citizen to experience and to enjoy.

This article is dedicated to these extraordinary public servants.

National Park Rangers History

Table Of Contents

- One Of America’s Most Dangerous Jobs

- America’s First National Park Under Siege

- U.S. Army Soldiers Were The Earliest Park Protectors

- America’s First Park Ranger

- The First African American Park Superintendent

- America’s First National Park Ranger

- Creation Of The National Park Service

- Early National Park Rangers

- First Female Ranger

- First To Go From From Park Ranger To NPS Director

- Ranger Stories

- What Park Rangers Do

- Take A Deeper Dive

- About More Than Just Parks

- Meet The Parks Brothers

One Of America’s Most Dangerous Jobs

In my travels through America’s National Parks, I’ve come across people who envy the lives and the livelihoods of our national park rangers. “How wonderful to get paid for basking in the sunshine and being surrounded by all of this splendor,” one woman commented to me.

From a man I met at the Grand Tetons, I remember the following remark, “ I can’t believe they pay these folks for this incredible opportunity. Shouldn’t these park rangers be paying Uncle Sam?”

I politely responded “No.” The gentleman walked off somewhat perturbed because I didn’t see eye-to-eye with him.

If You Cannot Work 10 – 12 Hours A Day, Don’t Fill Out The Attached Blank

The 2nd Director of the National Park Service, Horace Albright, would have also disagreed with this tourist. In a letter to prospective ranger candidates, Albright had this to say, “The duties are exacting and require the utmost patience and tact at all times.“

“A ranger’s job is no place for a nervous, quick-tempered man, nor the laggard, nor the one who is unaccustomed to hard work.”

“If you cannot work hard ten or twelve hours a day, and always with patience and a smile on your face, don’t fill out the attached blank.” (Source: Horace Albright, The Birth of the National Park Service)

“Ranger Danger”

The job of a national park ranger requires incredibly long and often times difficult hours of dedicated service. More than that, however, the job is not without its risks for those who put on the uniform.

According to Andrea Lankford, who is a former national park ranger and has written a fascinating account of the life of national park rangers. Lankford writes:

“In the United States, a park ranger is more likely to be assaulted in the line of duty than is any other federal officer, including those who work for the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco & Firearms (ATF); the Secret Service; and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA).”

“A park ranger is twelve times more likely to die on the job than is a special agent for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). In the light of such numbers, some describe park rangers–like grizzly bears, wild orchids and sea turtles–as ‘endangered.’”

Source: Andrea Lankford, Ranger Confidential: Living, Working and Dying in the National Parks

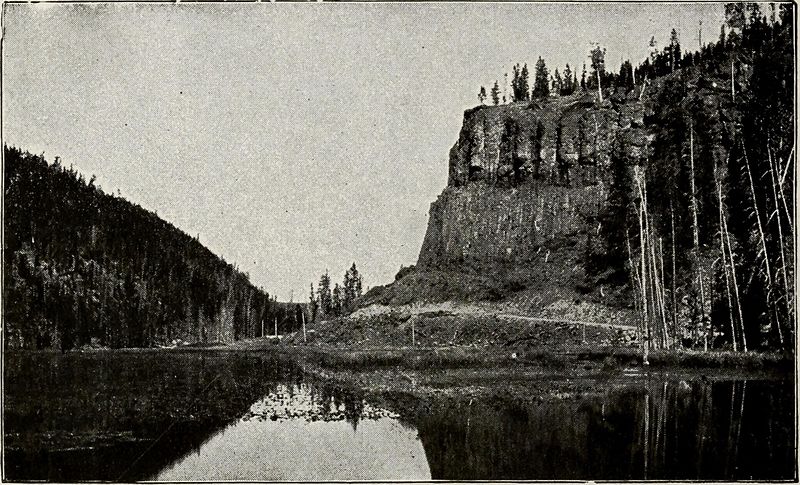

America’s First National Park Under Siege

Yellowstone National Park was America’s first national park. It could just as easily have been its last.

The park was established by an act of Congress which was signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872. Ten years later, however, Yellowstone had become endangered due to its lack of protections.

A contract, which was negotiated between the Department of the Interior and the Yellowstone Park Improvement Company, gave the company the right to “rent” the park out to private parties.

These groups could do whatever they wished. This included the wholesale slaughter of the park’s animals.

RELATED: 10+ FASCINATING Yellowstone National Park Facts You Probably Didn’t Realize

George Bird Grinnell

For early environmentalists, like George Bird Grinnell, efforts to defile Yellowstone meant the ultimate destruction of some of America’s most precious lands.

Grinnell was the editor and publisher of Forest and Stream, which was an influential magazine featuring hunting, fishing and other outdoor activities in the United States. Proving that the pen is mightier than the sword, he sounded the alarm in a series of blistering editorials.

America’s First Environmental Activist understood that America was at an inflection point where the Age of Industry, which had catapulted the U.S. economy to the global forefront, was now in a position to pursue its profits in reckless and dangerous ways. These included the exploitation and potential destruction of the American West.

Yellowstone National Park Protection Act

Under George Grinnell’s direction, there were weekly editorials promoting legislation to protect Yellowstone thereby ensuring it would be managed solely by the federal government. He also recruited prominent politicians, such as Commissioner of the U.S. Civil Service Theodore Roosevelt, Speaker of the House of Representatives Thomas Reed, and others, to lead the fight in Washington.

By focusing on the imminent threat to Yellowstone from unbridled corporate interests and the poaching which they encouraged, Grinnell was instrumental in helping to secure passage of the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act in 1894.

RELATED: America’s First Environmental Activist

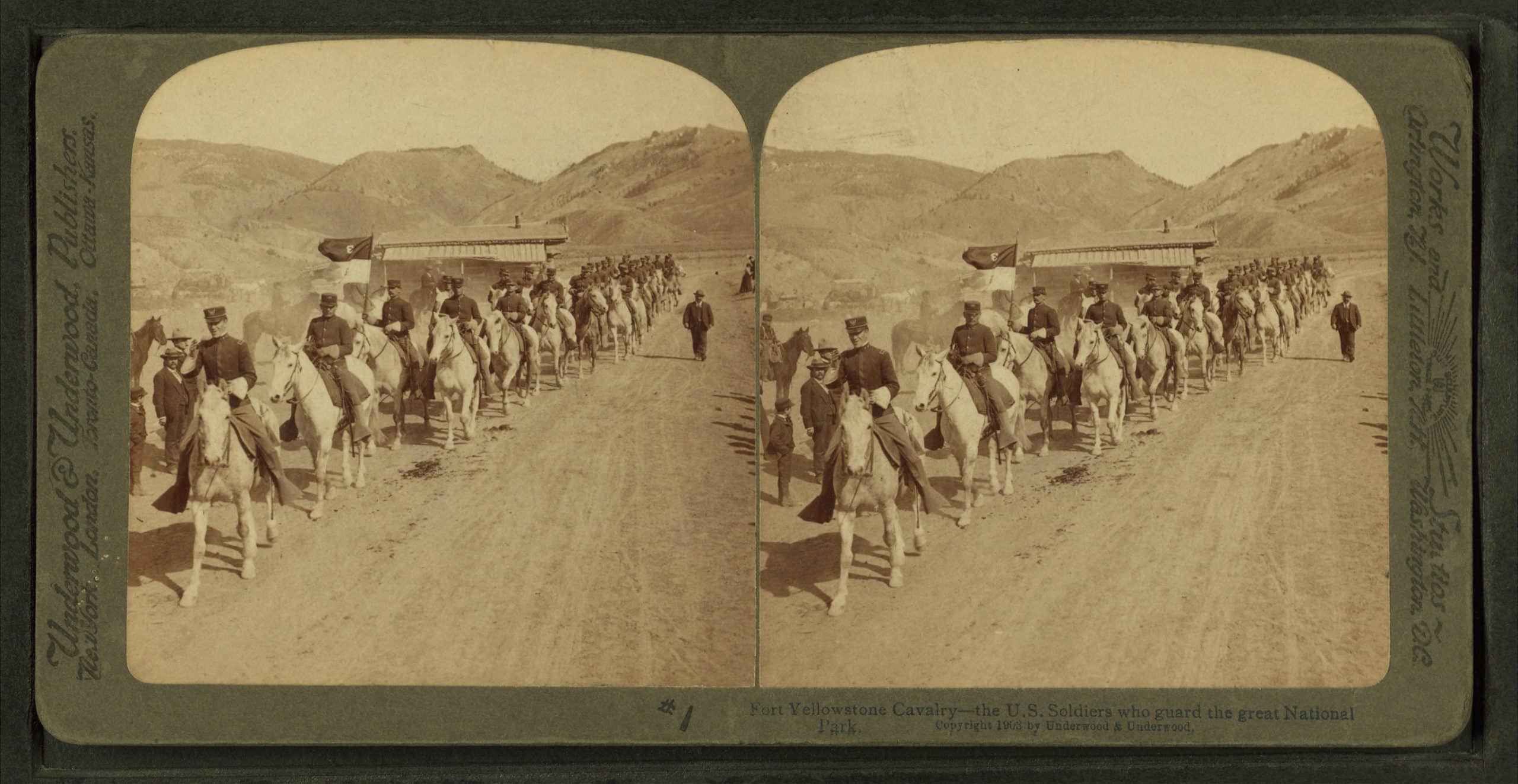

U.S. Army Soldiers Were The Earliest Park Protectors

The earliest protectors of our national parks were not the park rangers we’ve grown accustomed to seeing when we visit these special places. There was no National Park Service in the 19th century and there were no national park service rangers.

Before the National Park Service, Yellowstone was guarded by the U.S. Army. Without these soldiers, we might not have any national parks today.

From 1891 to 1914, Yosemite, Sequoia & General Grant (today Kings Canyon) National Parks were also under the protection of the U.S. Army.

“The officers and enlisted men have cheerfully endured many hardships and privations, and in the midst of great dangers steadfastly maintained a most gallant and zealous devotion to duty, and they may well be proud of the record made, and rest assured that the hard work undergone in the accomplishment of such important and valuable service to their country cannot fail, sooner or later, to meet with recognition and reward.”

-Benjamin H. Grierson, Colonel 10th U.s. cavalry

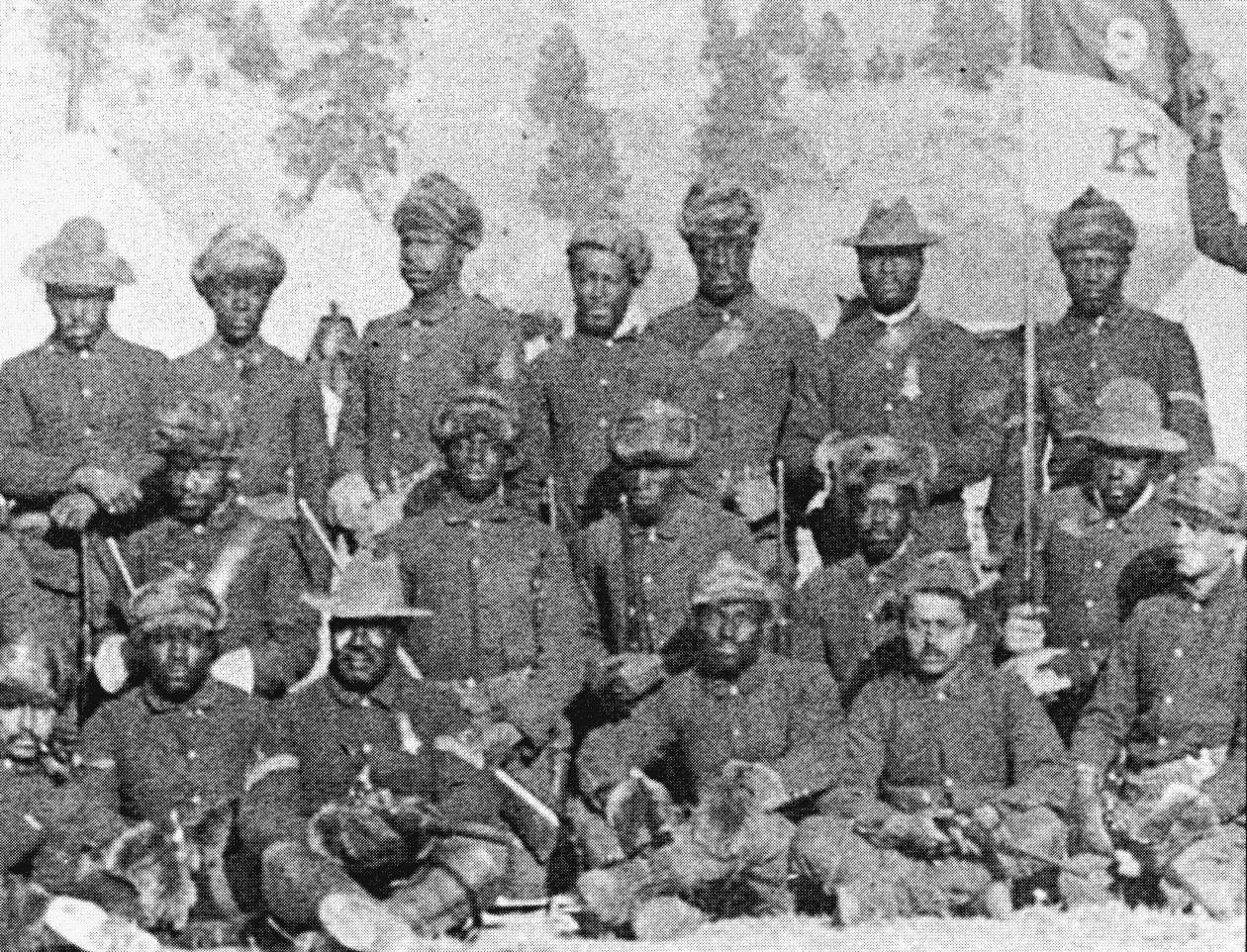

Buffalo Soldiers At The National Parks

Among the men who protected these parks, as National Park Ranger Shelton Johnson notes in his essay titled, “Invisible Men: Buffalo Soldiers of the Sierra Nevada,” were the 9th Cavalry or 24th Infantry. These units were comprised of the men who became known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

The Buffalo Soldiers were African-American infantry and cavalry regiments formed in 1866 after the Civil War. In their infancy, their primary purpose was to fight Indians on the western frontier, and it is from these engagements with cultures like the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Apache that the unofficial sobriquet of buffalo soldier was bestowed upon them.

Johnson writes, “Although their story has been celebrated for years, and there are histories, novels, and a few films that address their lives, the history of the Buffalo Soldiers of the Sierra Nevada has only recently been illuminated by the light of day.” (Source: Shelton Johnson, “Invisible Men: Buffalo Soldiers of the Sierra Nevada”)

RELATED: 20 BEST Black History Sites In America For You To Visit

“Fourteen Years Of Corrupt Or Incompetent Management”

The soldiers of the U.S. Army, like the cavalry in so many of Hollywood’s old western films, arrived in the nick of time to discover a park that was in danger of being destroyed.

As writer Jim Morrison notes, “Fourteen years of corrupt or incompetent management by political appointees threatened its [Yellowstone’s] existence. There had been little protection of the park’s natural wonders. Congressional funding was an afterthought.” (Source: Jim Morrison, “How The U.S. Army Saved Our National Parks,” Smithsonian Magazine)

As one of the earliest Superintendents of Yellowstone National Park and later the Second National Park Service Director, Horace Albright would agree with Morrison’s grim assessment.

Albright, writing long before Morrison published his article, had this to say, “In the first fourteen years of its existence as a park, Yellowstone had virtually no protection: sportsmen and commercial hunters shot bison, ranchers let their cattle graze within the boundaries, and visitors threw objects of all kinds into geysers and fumaroles to see what would happen–some even poured in soap flakes, hoping to trigger eruptions.”

“On one occasion tourists traveling to the park by stagecoach were attacked by Nez Perce Indians fleeing the army.” (Source: Horace Albright, The Birth of the National Park Service: The Founding Years, 1913-33)

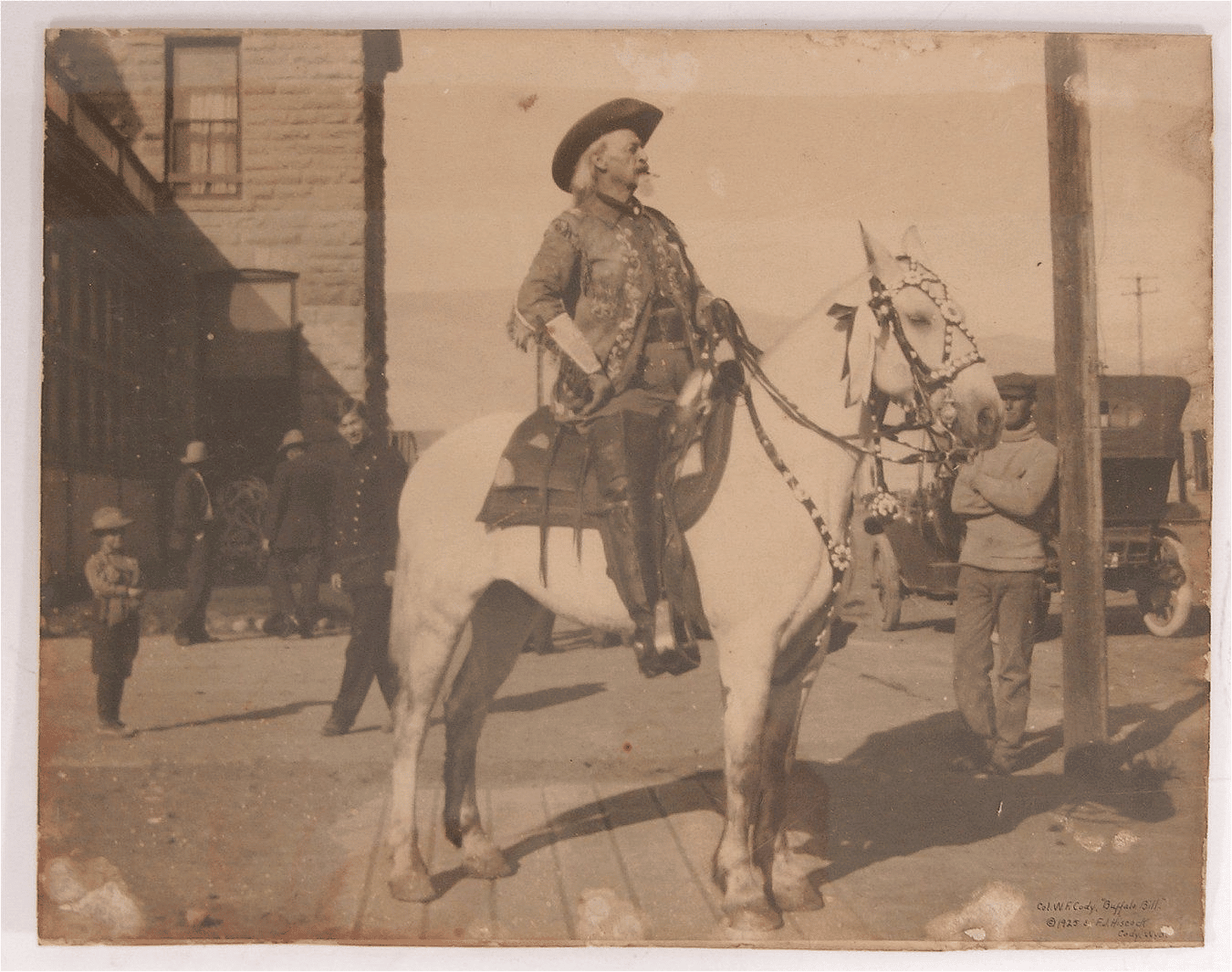

Prior to the arrival of the U.S. Army, poaching was so rampant that Buffalo Bill Cody wrote a letter to the New York Sun pleading for federal protection.

Acres Of Precious Land Were Being Devastated

And it wasn’t just the slaughter of animals which threatened the continued existence of Yellowstone. Park lands were also being used for cattle and sheep grazing, timber was being cut down at an alarming rate and fires were burning unrestrained. In short, acres of precious land were being devastated.

The soldiers quickly put a stop to this wanton destruction. The military administration at Yellowstone proved to be a model for the early management of Yosemite, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in California.

According to Lee Whittlesey, who worked at Yellowstone for 35 years and served as the park historian since 2000, “I would submit the Army went a long way towards protecting an area that had very little protection and turned it into a place of relative tranquility, where tourists could enjoy it while also protecting its wonders.” (Source: Jim Morrison, “How The U.S. Army Saved Our National Parks,” Smithsonian Magazine)

With the creation of the National Park Service in 1916 and America’s entry into the First World War one year later, the soldiers began to withdraw. Their job was done, but the question remained: Who would replace them?

National Park Rangers History

America’s First Park Ranger

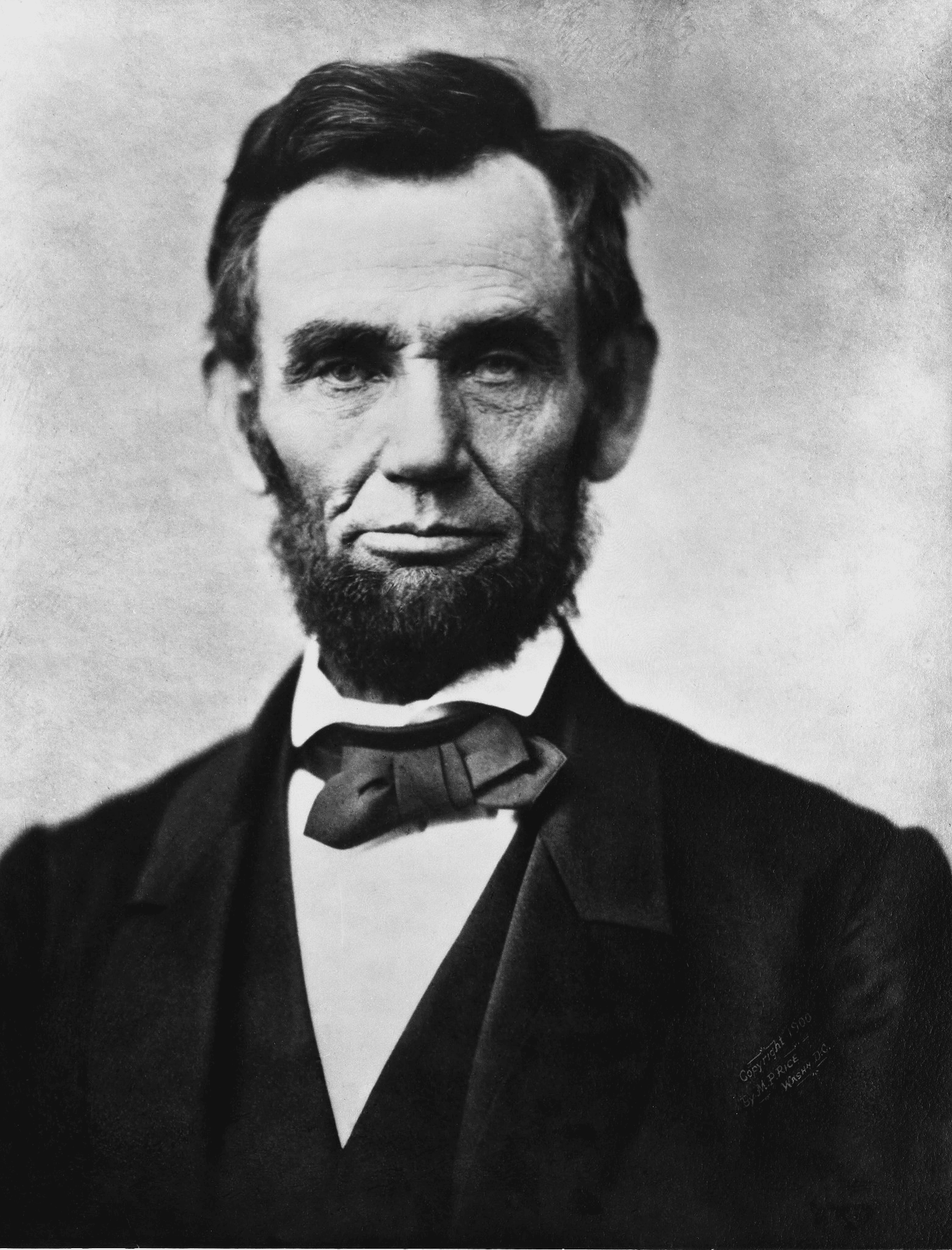

While it is not America’s first national park, Yosemite was the first park to receive the protection of the federal government. On June 30, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Act into law.

Why wasn’t it America’s first national park you might ask? Since the park remained, for the time being, under the custody of the state of California rather than the federal government, Yosemite was not (yet) considered a national park.

Yosemite became a national park on October 1, 1890, eighteen years after Yellowstone, America’s first national park, was created.

Nevertheless, this act did place the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove into the public trust. Sixty square miles were set aside for the state of California and made into a state park.

This would be the first area set aside anywhere in the world by a government for no reason other than its scenic value and the enjoyment of its citizens.

RELATED: 10 SHOCKING Yosemite National Park Facts That Will Change How You View The Park

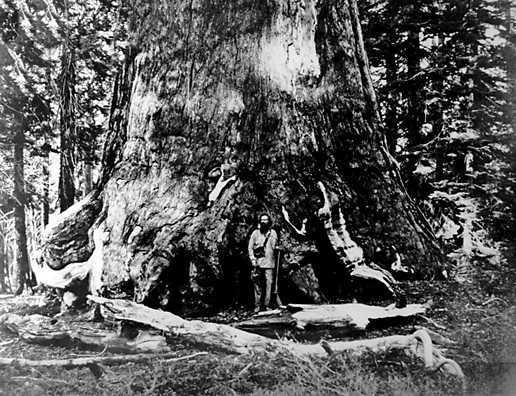

Galen Clark

Who would serve as the guardian of this newly protected land?

On May 21, 1866, Yosemite pioneer Galen Clark was officially named as the “Guardian of Yosemite.” Clark was duly authorized to protect these beautiful areas.

He was the first private protection officer ever designated to safeguard America’s public lands.

Galen Clark was America’s first park ranger.

In 1870, Clark made an arrest, which was a first within a park. It was for a felled giant pine tree. The men were found guilty and each fined $20 each by a local judge.

Clark was even made a special sheriff’s deputy in 1875 to help evict a nearby and longtime associate from his home in the valley. (Source: Charles R. “Butch” Farabee, Jr., National Park Ranger: An American Icon)

As later rangers would do, Clark also fought fires and protected the precious resources of the region. He shared his knowledge of the area through his efforts as a guide and an educator.

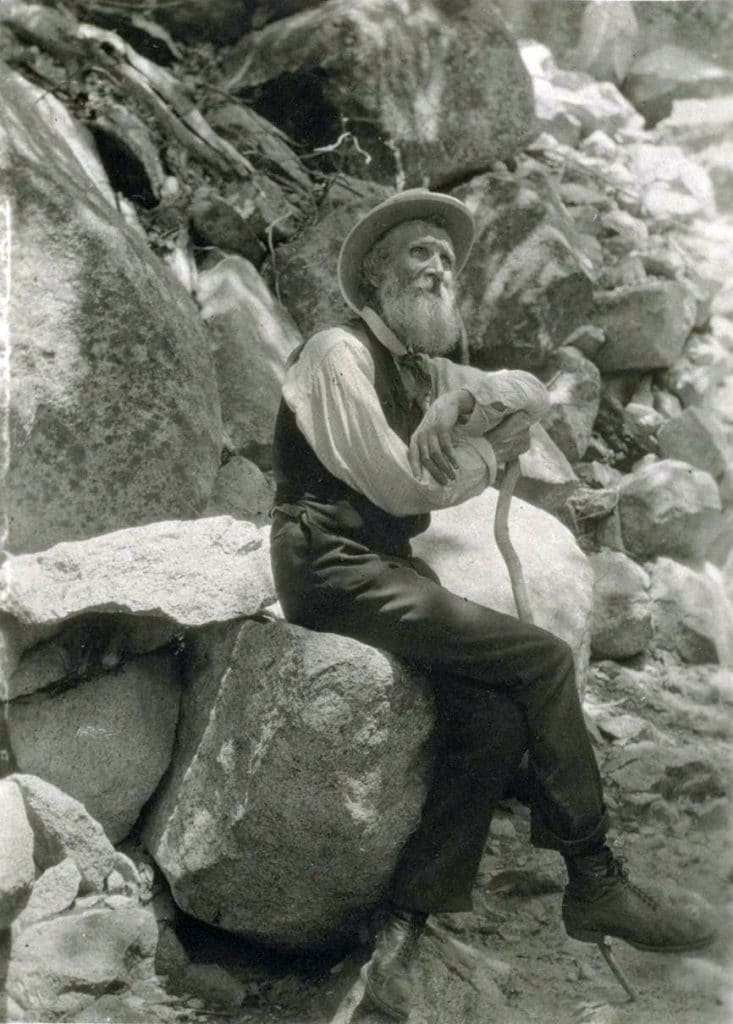

Galen Clark & John Muir

John Muir, who many consider to be the “Father of the National Parks,” referred to Clark as “the best mountaineer I ever met and one of the most sincere tree-lovers I ever knew.”

Muir met Clark at his Wawona ranch during the legendary botanist’s first visit to Yosemite.

Over the years, the two outdoorsmen made many wilderness sojourns together in which Clark scrambled through thick chaparral brush in the easiest way.

On one 1872 trip, Clark helped set stakes in an ice field on the slopes of Mount Maclure as part of Muir’s glacial research. Deemed the best mountaineer that Muir ever met, Clark sought few comforts when outdoors. He was even rather careless about selecting a bed for the night.

“He would lie down anywhere on any ground, rough or smooth, without taking pains even to remove cobbles or sharp-angled rocks protruding through the grass or gravel,” Muir wrote. (Source: NPS)

Clark wrote a wonderful account of his time spent in the Yosemite appropriately titled The Yosemite Valley.

CHECK OUT: 10+ AMAZING John Muir Facts-America’s Greatest Conservationist

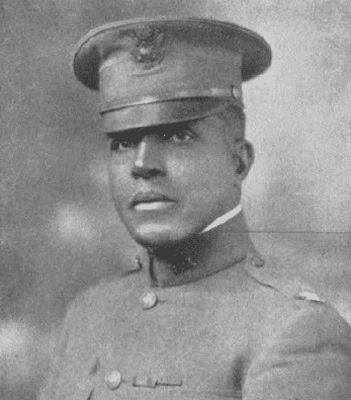

The First African American Park Superintendent

For almost 30 years, I taught high school history. What impressed me most about the field of history are the amazing stories of men and women whose contributions changed the course of human events. In doing so, they helped to bring about the world we have today.

The people we know, however, are relatively few when compared to the ones we don’t. When you start to do a little digging, you begin to realize that the stories of the ones we don’t know anything about can be just as interesting.

A case in point is Galen Clark, America’s first ranger. Another case in point is Colonel Charles Young.

Young was the first African American to serve as superintendent of a national park.

He Lived A Truly Extraordinary Life

Born as a slave during the American Civil War, Charles Young lived a truly extraordinary life. He was the first African American to graduate from a white high school in Ohio.

In 1884, Young defied the odds winning an appointment to West Point through a competitive military examination.

After confronting the racism which was typical of his era, Young emerged as only the third African American to graduate from West Point–America’s most prestigious military academy.

Superintendent Of Sequoia & General Grant National Parks

Young served as a cavalry officer. He then became the captain of an all-black regiment at San Francisco’s Presidio. Young rose through the military ranks to become one of the most respected leaders of his time.

His career path would take an interesting turn, however, when managing the national parks became the responsibility of the U.S. Army beginning in 1891.

Young was assigned to take his troops to Sequoia and General Grant (what is now Sequoia National Park and a small portion of Kings Canyon National Park).

It was during the summer of 1903 that he made history by becoming the acting superintendent of these two parks. He was the first African-American to hold such a position.

CHECK OUT: 20 BEST Black History Sites In America For You To Visit

“A journey through this park and the Sierra Forest Reserve to the Mount Whitney country will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains just as they are, with their clothing of trees, shrubs, rocks, and vines, and of their importance to the valley’s below as reservoirs for storage of water for agricultural and domestic purposes. In this, then, lies the necessity of forest preservation.”

Charles Young, 9th Cavalry, Sequoia National Park, 1903

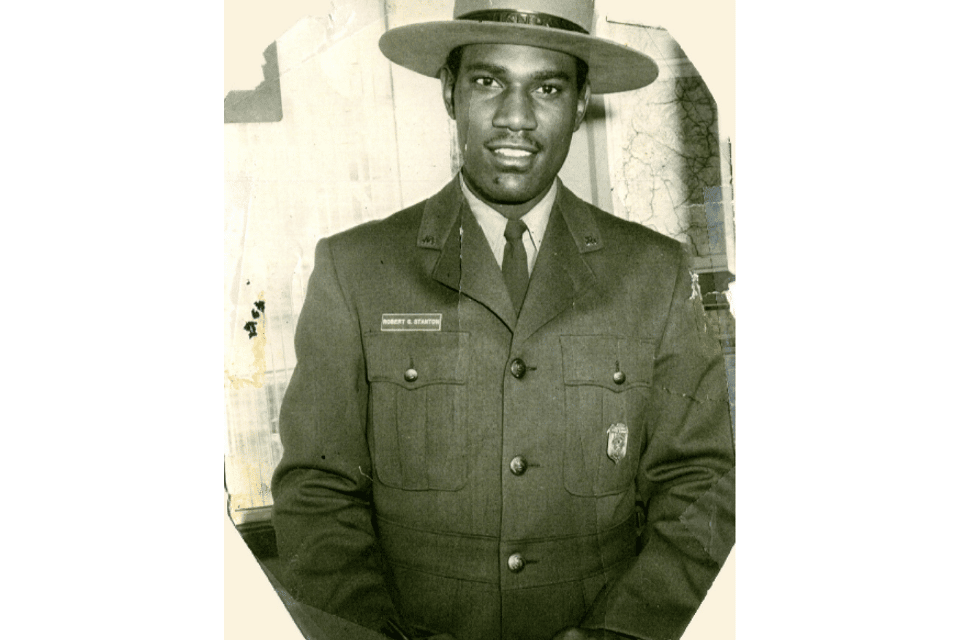

It Would Be 67 Years Before The Next African American Would Be Appointed Superintendent Of A National Park

While Charles Young was appointed superintendent in 1903, the National Park Service (NPS) would not be created for another thirteen years. And, it would be an additional fifty-four years before the NPS would appoint its first African-American Park Superintendent.

That honor would go to Robert Stanton.

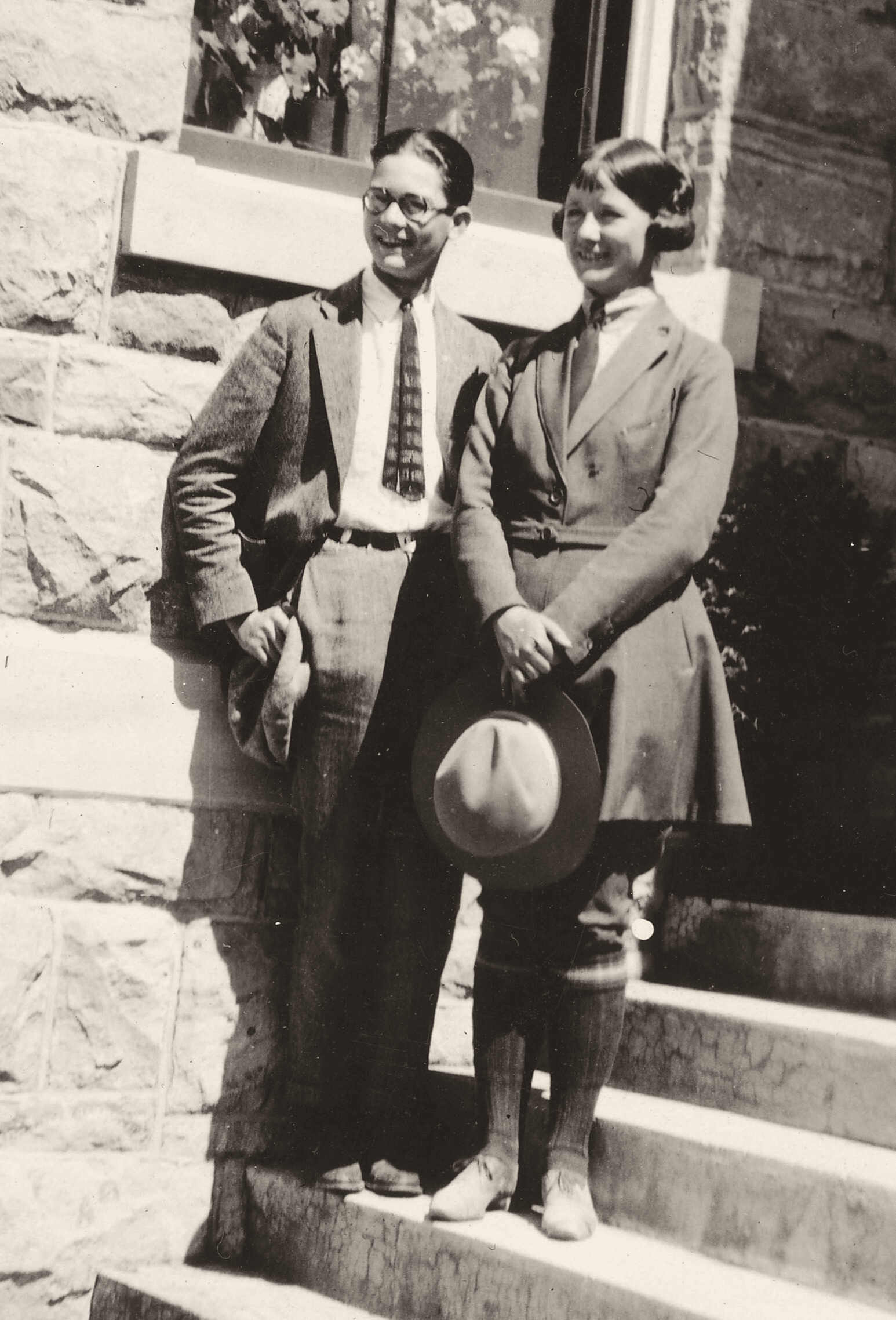

Stanton left his Texas home as a college student in 1962 to begin his long and important career with the National Park Service. Under the leadership of Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, the Department of the Interior was actively recruiting more Black people in the 1960s.

Stanton was recruited as a student at Huston-Tillotson, a historically Black college. At the time, there was just one Black park ranger in the entire service.

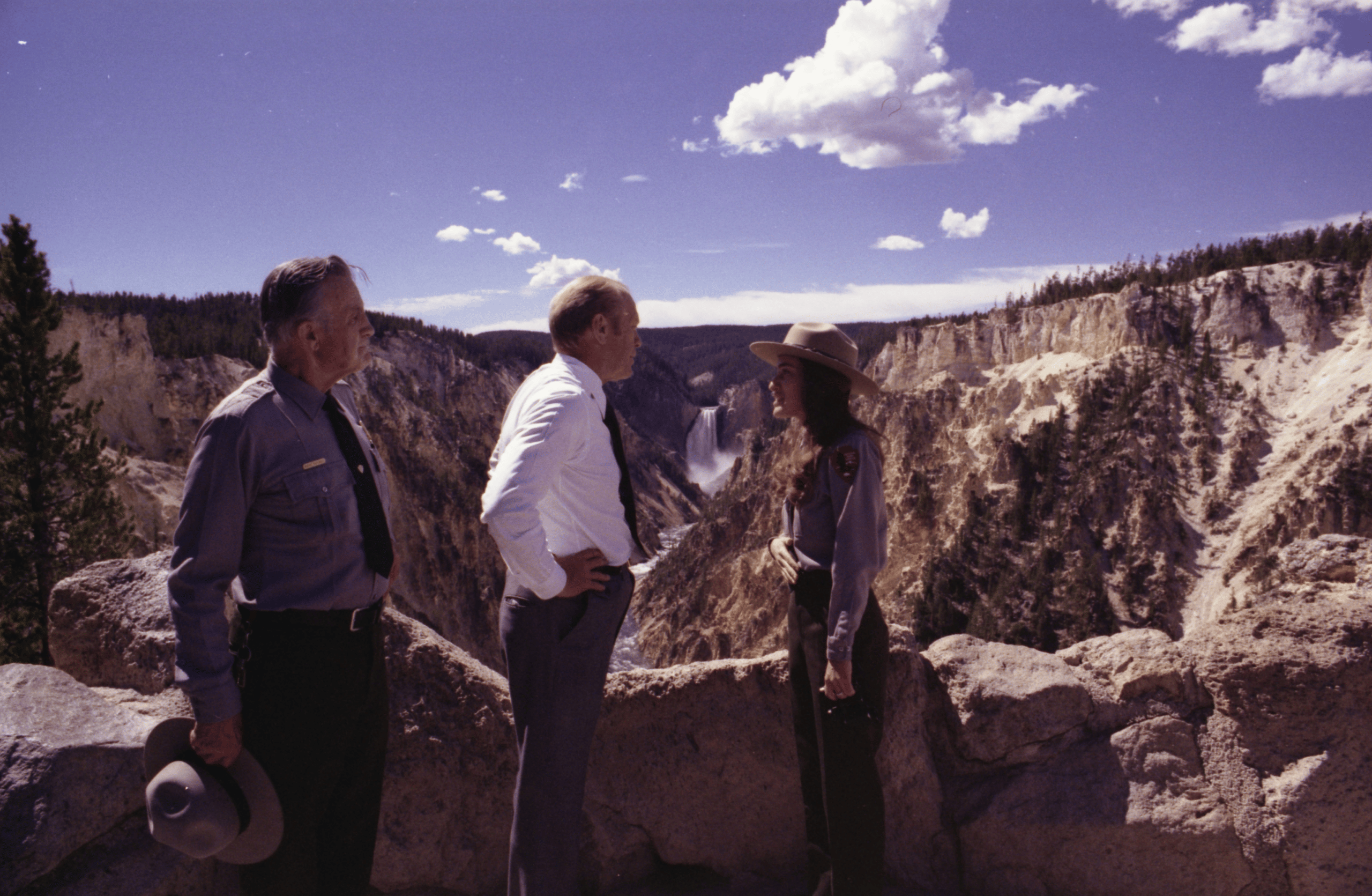

One Of Three African American Rangers At Grand Teton

Robert Stanton went on to become one of three African-American national park rangers at Grand Teton National Park.

As Stanton notes in an interview, “It was not so much the grandeur, the natural and magnificent beauty of Teton, year-round snowcapped mountains, etc.,” he says.

“But what was really defined for me was the quality of the professional staff at Grand Teton… I can say without any hesitation that the three African Americans, including myself, working at Grand Teton in ’62 were warmly and truly welcomed to the workforce. It spoke volumes about the quality and the professional integrity of those who were there at Grand Teton in 1962.” (Source: Buckrail)

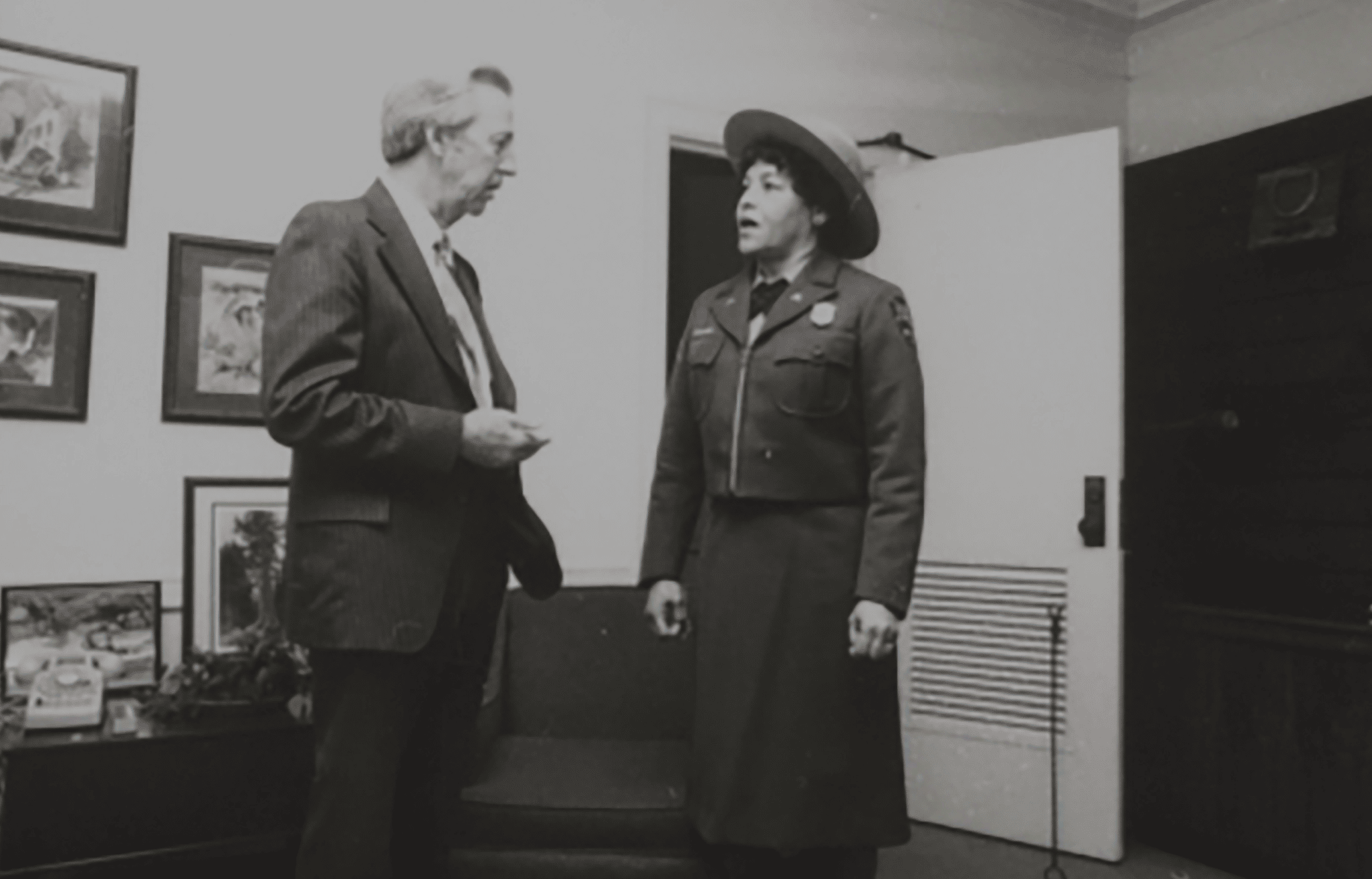

The First African-America Director Of The National Park Service

Stanton went on to become the National Park Service’s first African American superintendent in 1970 and its first African-American director in 1997.

Under Stanton’s leadership, NPS took steps to increase staff diversity and recognize and protect cultural and historic sites, particularly as they related to the contributions of historically underrepresented people in the United States.

He also worked tirelessly to strengthen the agency’s public programs in order to increase park accessibility and better serve historically underrepresented people.

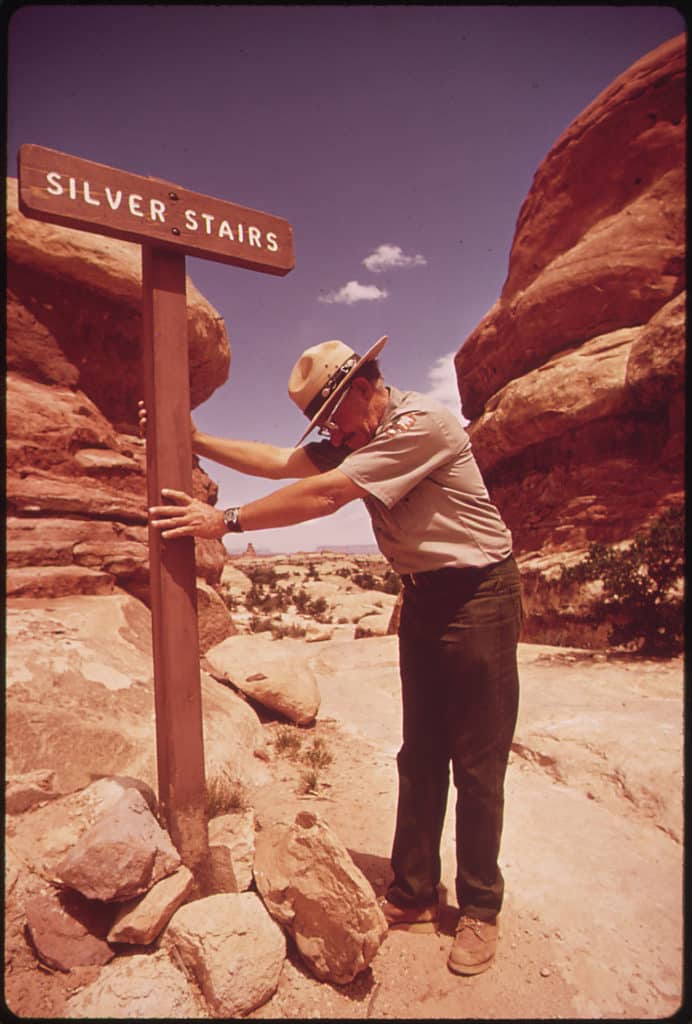

America’s First National Park Ranger

To Galen Clark goes the honor of being America’s first ranger, but Yosemite was not a national park at the time so the honor of being America’s first national park ranger would go to someone else.

That someone else began his park career working as a gamekeeper at Yellowstone in 1880.

Harry S. Yount had served as a Union soldier during the Civil War. Afterwards, he spent his time in the American West working as a bullwhacker (a driver of an ox wagon or other heavy freight wagon), guide and doing various other jobs.

While hunting was legal, too much wildlife was being slaughtered. “Rocky Mountain Harry,” as he was known at the time, was hired by Yellowstone National Park to protect endangered animals from commercial hunters. After fourteen months, he quit his job complaining that the park was simply too large for one man to patrol.

While his official job title had been “gamekeeper,” later National Park Service (NPS) historians would credit Yount as being the nation’s first “national park ranger.”

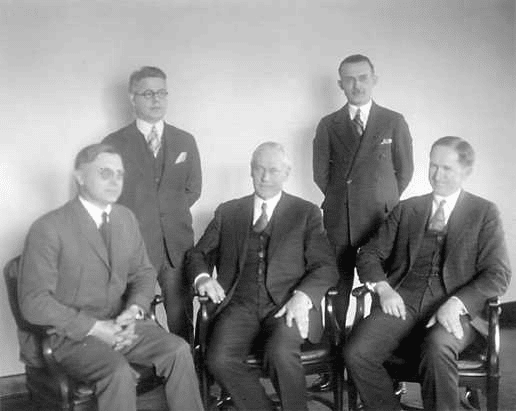

Creation Of The National Park Service

As Horace Albright writes in Creating The National Park Service: “One of the first things the new partnership of Mather and Albright faced was park administration.“

“A lot of Mather’s criticism had been about the miserable conditions in the national parks he had visited, not just the rundown physical aspects, but the dirty, unhealthy conditions of lodging, food, and sanitary facilities. He blamed most of these on the men in charge of the parks.” (Source: Horace Albright, The Birth of the National Park Service: The Founding Years, 1913-33)

After the Hetch Hetchy controversy, the Sierra Club and its environmental allies petitioned the government for stronger protection of national parkland through the creation of a unified federal service to manage the parks.

On August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed legislation creating the National Park Service through the National Park Service Organic Act.

It would fall to Stephen Mather to create the professionalized service responsibility for maintaining our national parks.

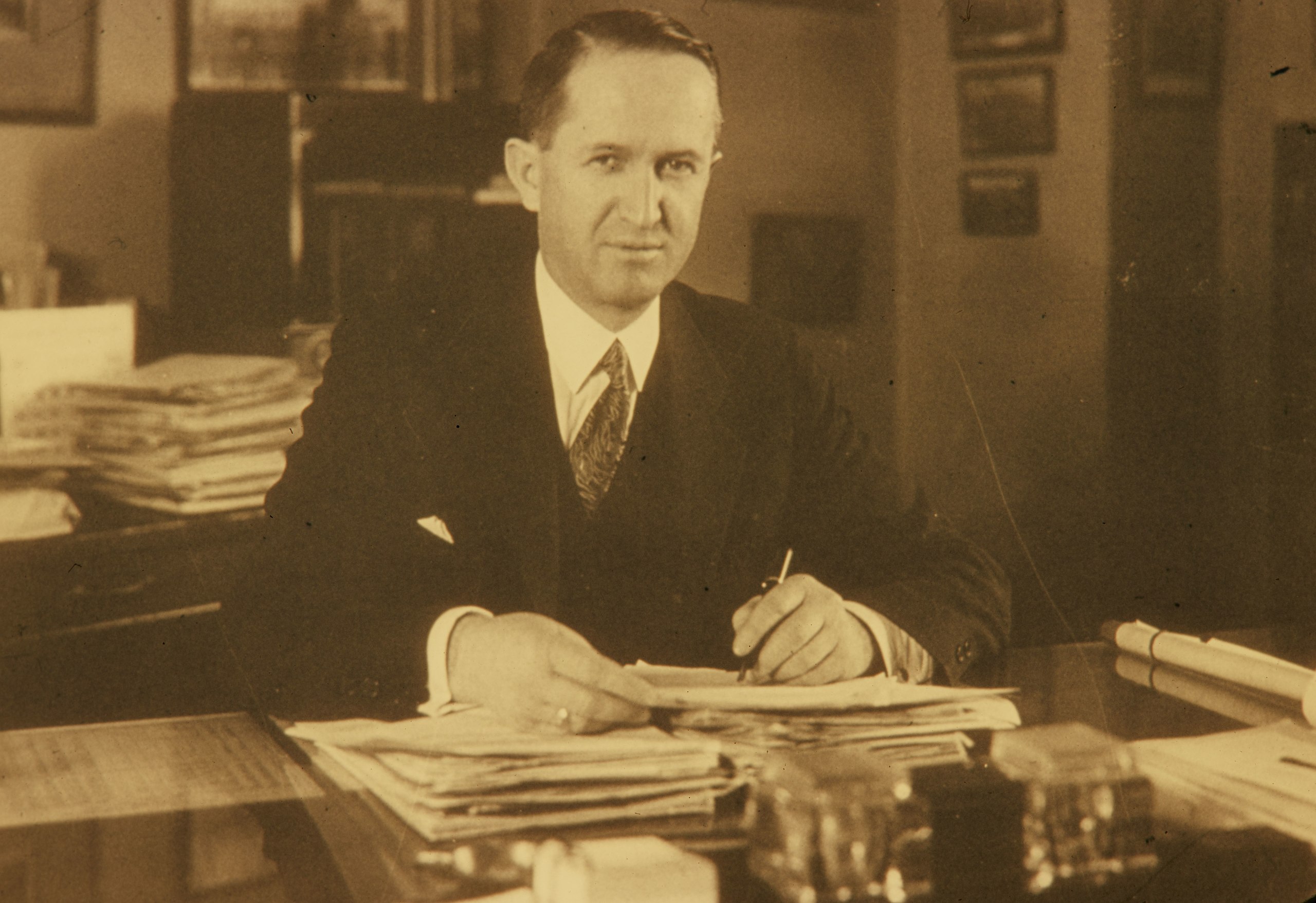

Stephen Mather

Stephen Mather became the first head of the National Park Service. He introduced concession operations into the National Parks where tourists could purchase food and other basic necessities. He also promoted the creation of a highway system that would make national parks more accessible by automobile.

The new agency’s mission was to conserve the scenery, natural and historic objects and wildlife within the parks and to “provide for the enjoyment of the same in such a manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

RELATED: Meet The Real Life Batman & Robin Of The National Parks

National Park Rangers History

Early National Park Rangers

The starting pay for rangers in 1923 was only one thousand dollars a year though they could eventually work their way up to $1,320. Out of that salary, however, they had to purchase their own uniforms and pay for their own food. Despite the pay, the National Park Service was swamped with applicants.

Stephen Mather and Horace Albright were the guiding force behind the National Park Service during its formative years. Mather wanted the park ranger position to be a career as opposed to merely a job.

In his 1916 annual report, he wrote the following:

“The longer a man is in the service the more valuable he is, and, therefore, I think a ranger should enter the service with the desire of making it his life’s work, and after the service is once fully organized, promotion to higher positions should be made in the corps, so that each man would have the fullest incentive to give his best service, knowing that advancement would be based on character and general efficiency.” (Source: Horace Albright, The Birth of the National Park Service: The Founding Years, 1913-33)

The Earliest Park Rangers

The earliest park rangers were picked for their skill in woodsmanship and wilderness survival. Among them were Jim McBride, Harry Trishman and Raymond Little. These men were among the first to serve as national park rangers at Yellowstone National Park.

In 1926, President Calvin Coolidge issued an executive order revoking the practice of appointing park rangers without examination. Coolidge directed the Civil Service Commission to prepare qualifications and develop a competitive examination for national park rangers.

Among the duties of a national park ranger were the following: knowledge of methods of fighting forest and prairie fires; packing of horses and mules; habits of animals; ability to ride and handle horses; construction of fire lines and trails; reading of topographic maps and compass; tact in handling people; cooking; use of firearms; driving motor cars and motorcycles; and in those parks where needed, skill on snowshoes and skis; incidental clerical and information work. (Source: Horace Albright, The Birth of the National Park Service: The Founding Years, 1913-33)

First Female Ranger

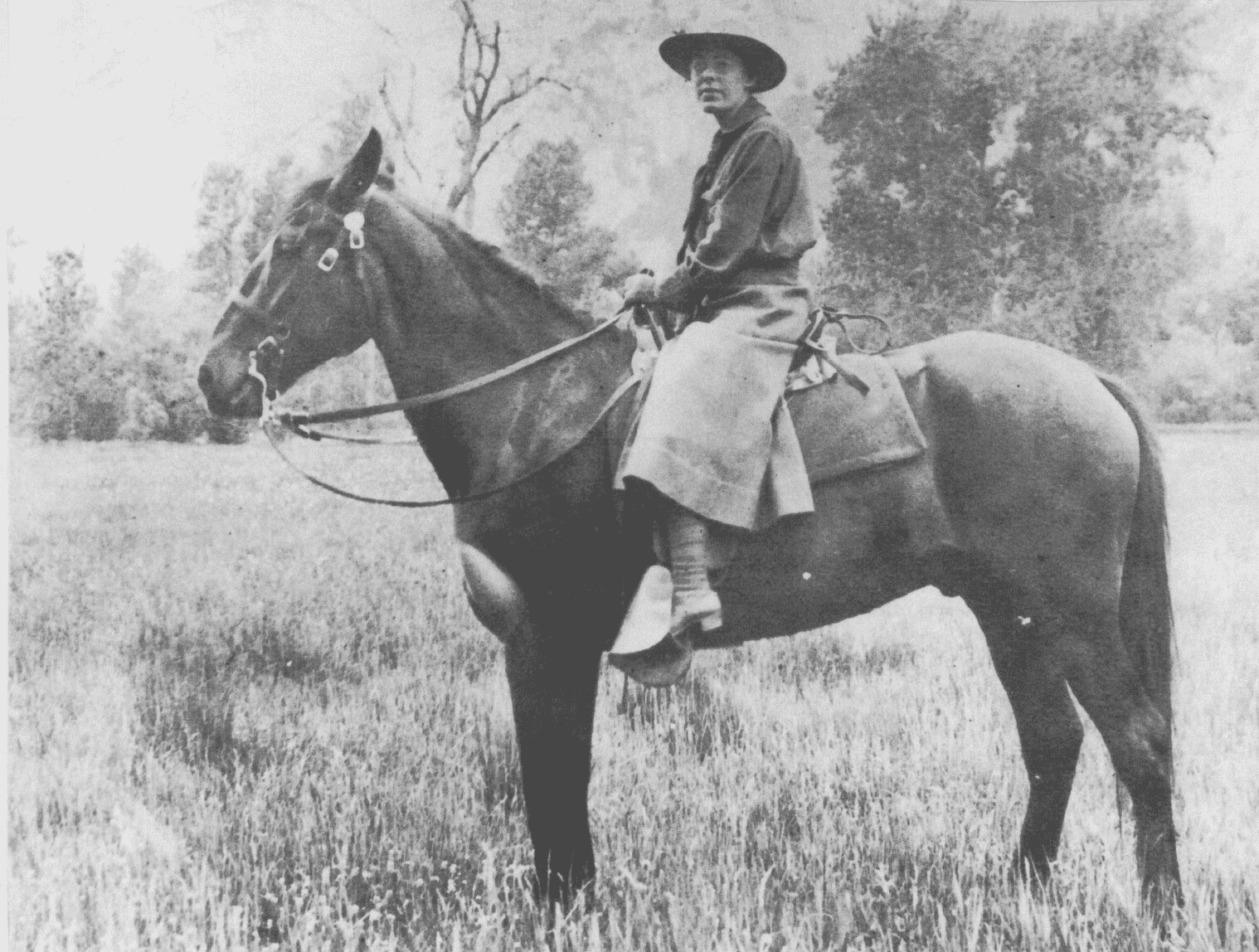

Clare Marie Hodges was the first woman ranger in Yosemite National Park and is generally considered to be the first fully commissioned female ranger in the National Park Service.

Hodges first visited Yosemite at the age of fourteen, arriving after a four-day horseback ride. Falling in love with Yosemite Valley, Hodges returned to the valley in 1916 to teach at the Yosemite School.

Two years later, during World War I, Hodges applied to Park Superintendent Washington B. Lewis for a job as a park ranger. During the war, due to shortages of available male applicants, women were often selected to serve in non-traditional roles, such as police officers and factory workers.

Much to Clare’s surprise, Lewis hired her as a ranger in spring 1918. Though it would not become standard operating procedure for female rangers until the 1970s, Hodges wore the same uniform, Stetson hat and badge, as the men.

She had the same duties and responsibilities as her male counterparts. The only exception was her refusal to carry a gun. (Source: Sierra College)

Other Female Pioneers

Other female pioneers included Helene Wilson, who was hired only six weeks after Hodges, to serve at Mount Rainier National Park; Isabel Bassett Watson, who became Yellowstone’s first female naturalist in 1920; and Marguerite Lindsley who was born and raised in Yellowstone and the daughter of the park’s chief clerk.

Lindsley was an accomplished horsewoman, cross-country skier and trans-continental motorcyclist who had a broad knowledge of the history of the park. She enjoyed a ten-year career in the National Park Service. Lindsley became the first permanent female ranger-naturalist.

First To Go From From Park Ranger To NPS Director

Unlike Claire Marie Hodges, Russell E. Dickenson shattered a different ceiling.

He began his NPS career as a ranger at Grand Canyon National Park in 1946. Dickenson went on to serve in a wide range of park and central office assignments – most prominently as head of National Capital Parks, deputy director, and Pacific Northwest regional director – before ascending to the directorship in May 1980.

As the first Director of the NPS to have risen from ranger to director, Dickenson was enthusiastically welcomed to the job. He was supported in his effort to restore organizational stability after a succession of short-term directors.

Prior to this, Dickenson had been the only Interior Department bureau chief to be retained by the incoming Reagan administration in 1981. He obtained its support and that of Congress for the Park Restoration and Improvement Program, which devoted more than a billion dollars over five years to park resources and facilities.

Dickenson retired in March of 1985. He died in 2008.

National Park Rangers History

Ranger Stories

In researching and writing this article for More Than Just Parks, I came across so many wonderful stories of national park rangers. Unfortunately, I cannot share all of these stories with you as there are far too many.

Instead, I will share three of my favorites which span the decades from the early years of the NPS to more recent times.

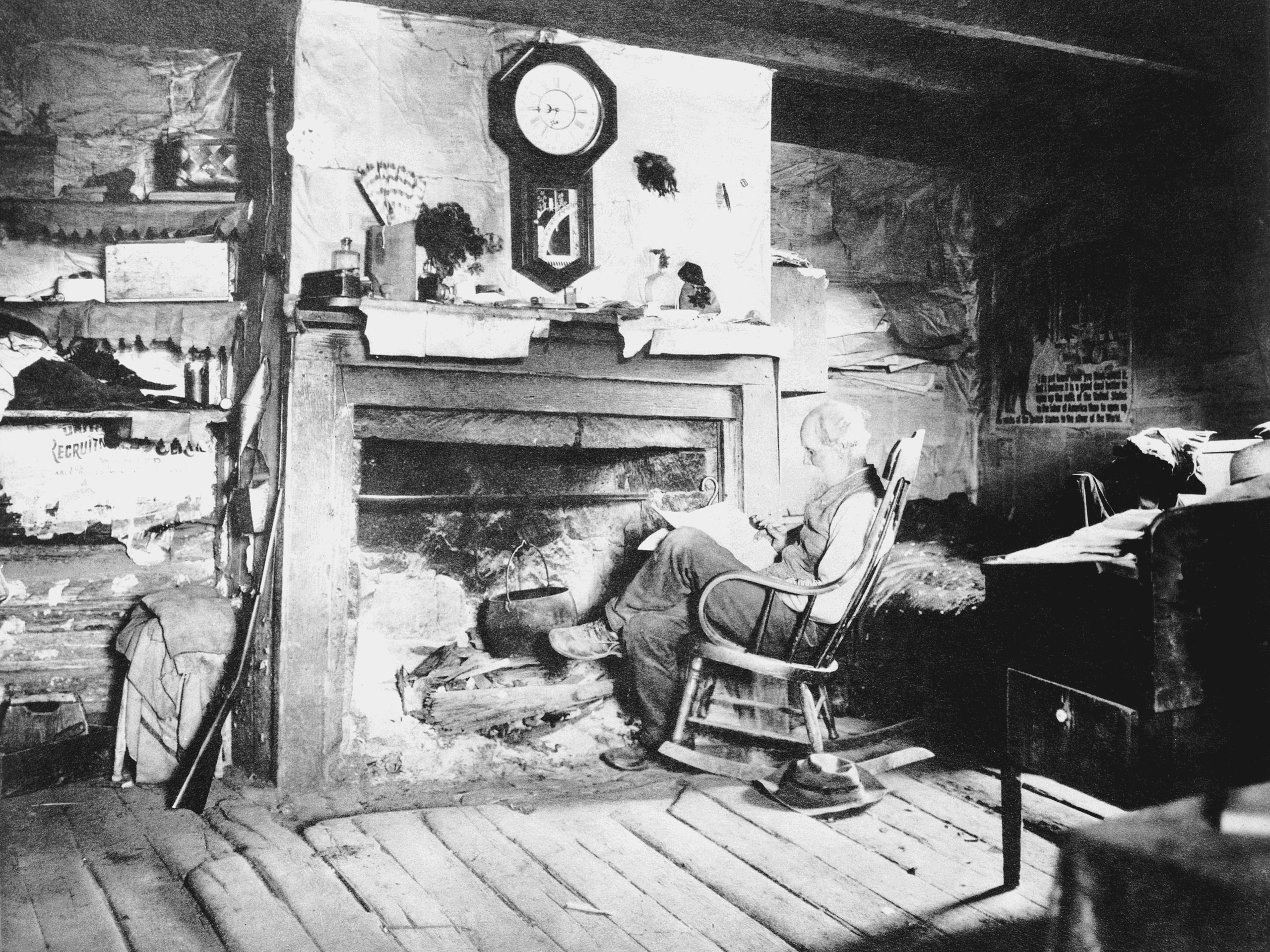

Colonel John White

One of my favorites is the story of Colonel John White. White was an Englishmen who joined the Philippine Constabulary in 1901, and rose to rank of colonel. He retired in 1914, but that’s only the beginning of his story.

Between 1916 and 1917, White was in Europe working with the Red Cross and the Rockefeller Foundation. He became an American citizen and then joined the American Expeditionary Force as a Signal Corps pilot during World War One.

White knew General John J. Pershing who was commander of the American Forces in Europe. He served as one of the provosts during the Paris Peace Negotiations in 1919.

After the war, White went to the National Park Service. He was eager to serve. While the NPS could not offer him a job commensurate with his experience (e.g., park superintendent), he was glad to take the job of a park ranger in the Grand Canyon.

A year later, French Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch, who had served as the Supreme Allied Commander in the First World War, went to Yellowstone. John White, who spoke fluent French, served as his tour guide.

He took Foch to the edge of the canyon and looked down. White asked Foch what he thought of all of this hoping for a memorable quote in reply which the NPS could use.

“Ah,” Marshal Foch said, “What a place to bring a mother-in-law!”

White later went on to serve as Park Superintendent at Grand Canyon, Sequoia, and General Grant National Parks, Death Valley National Monument, and as Director of Regions 3 and 4 from 1940 to 1941.

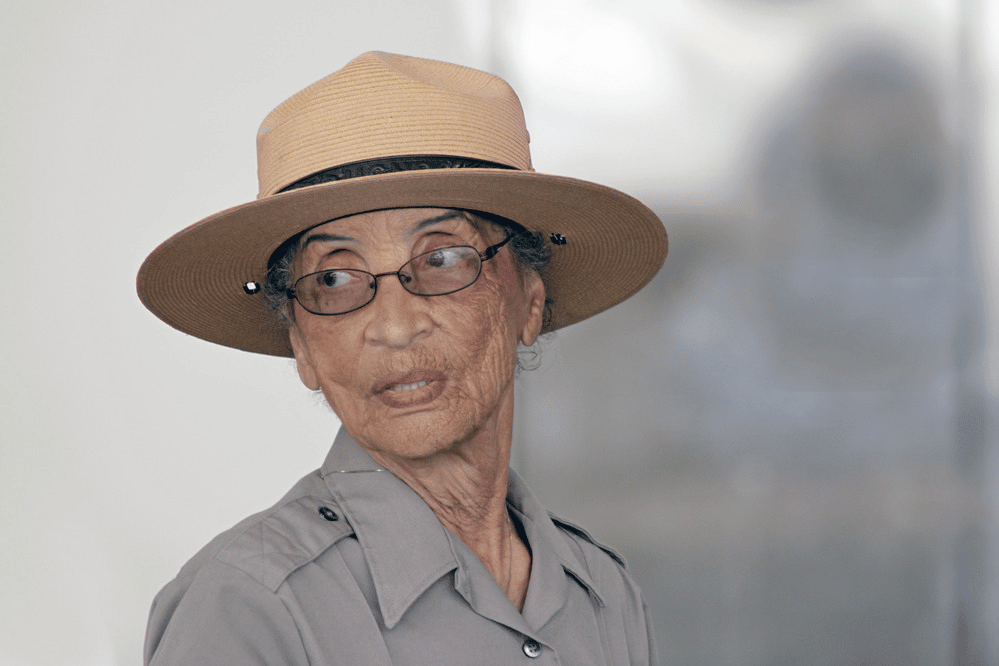

Betty Reid Soskin

And then there’s the story of Betty Reid Soskin. Betty graduated from Castlemont High School in Oakland during the World’s Fair at Treasure Island.

Betty worked in a segregated Union hall, Boilermaker’s A-36, during World War Two as a file clerk. In 1945, Betty and her husband, Mel Reid, founded one of the first black-owned music stores — Reid’s Records, which closed in the fall of 2019.

Betty went on to hold positions as staff assistant to a Berkeley city council member and as a field representative serving West Contra Costa County for two members of the California State Assembly: former Assemblywoman Dion Aroner and Senator Loni Hancock.

America’s Oldest Park Ranger

In the early 2000s, Betty participated in meetings with the City of Richmond and the National Park Service to develop the general management plan for Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park.

She worked with the NPS on a grant funded by PG&E to uncover untold stories of African-Americans on the Home Front during WWII, which led to a temporary position working with the NPS at the age of 84.

In 2007, Betty became a permanent NPS employee and has been leading public programs and sharing her personal remembrances and observations at the park visitor center.

In early 2019, a film produced by the Rosie the Riveter Trust, “No Time To Waste: The Urgent Mission of Betty Reid Soskin,” was released.

This documentary tells the story of Betty’s involvement with Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historic Park and the influence she has had on the NPS in telling untold stories, and in sharing her history in ways that inspire and challenge current social norms. (Source: NPS)

Jerry Bransford

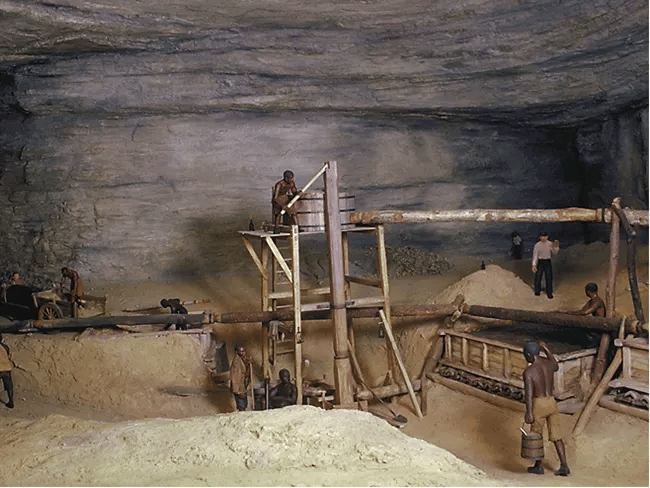

Jerry Bransford grew up just a few miles from Mammoth Cave National Park. As a kid, he knew a little of his family connection to the park, but as an adult he learned how much his family actually contributed to the history of the caves.

Bransford went to technical college. He was drafted into the Army in 1968 during the height of the Vietnam War. While training at Fort Knox, he met Barbara who lived in Glendale. They married in 1968. He served his two years and then resided in Glendale.

In 1972, he began a 30-year career at Dow Corning in Elizabethtown. After retiring, a new adventure began.

An Incredible Story To Tell

Jerry Bransford started working in 2004 as an interpretive ranger, a fifth generation guide at Mammoth Cave National Park. That’s when he began to share his family’s incredible story with the visitors.

Bransford’s father was born near Mammoth Cave in 1914, his grandfather in 1876 and, in 1849, his great-grandfather was born there into slavery.

His great-great-grandfather, Materson Bransford, was owned by an Englishman named Thomas Bransford who came to Virginia in 1791. Branford then moved to Nashville and was a member of the 1861 state senate. It turns out that he was not only Materson’s owner, but his father as well.

A man named Franklin Gorin had an idea to make the cave a tourist attraction, Bransford said. Gorin rented two slaves from Bransford, Materson, and another named Nicholas, to explore the caves and give tours.

Since that time, Bransford’s family had guided tours for 100 years before it was named America’s 26th national park in 1941. (Source: The News Enterprise)

“I’ve Been Chosen To Tell Their Stories”

The National Park Service officially assumed operations of Mammoth Cave in 1941. When the guide staff was assembled none of the black guides were asked to stay on as cave guides, including the 4th generation Bransfords: Clifton, Arthur, Eddie, Elzie, and George.

This ended a century of both black and white cave guides working alongside each other and the legacy of Bransfords guiding at Mammoth Cave. (Source: NPS)

“It’s not about Jerry Bransford,” he said. “I believe I’ve been chosen as a representative to tell their stories, things that went untold for more than 170 years.” (Source: The News Enterprise)

Through Jerry Bransford, the incredible story of the Bransford Family and their connection to Mammoth lives on.

National Park Rangers History

What Park Rangers Do

Now that you’ve read my article, I hope you have a better understanding of what our national park rangers do and why they are so very important.

The title “ranger” encompasses many responsibilities which most people don’t understand.

Below is a list of some of the “routine” activities performed by our national park rangers:

- Perform search and rescue

- Consult on environmental policies

- Enforce federal, state and local laws

- Provide emergency medical services

- Fly planes, pilot boats and SCUBA dive

- Flight structural fires and manage wildland fires

- Give interpretive talks and lead overnight walks

- Manage threatened and endangered plants and animals

- Act as coroners as well as Immigration & Naturalization officers

- Staff information booths and communications centers

- Perform criminal and internal investigations

- Record history and take oral interviews

- Do light maintenance and construction

- Raise the flag and operate elevators

- Research and collect scientific data

- Train people and write manuals

- Pick up litter and clean latrines

- Monitor air and water quality

- Shoe horses and pack mules

- Investigate accidents

- Operate jails

- Supervise

- Design websites

- Serve as “dog catchers”

- Oversee concession operations

- Intercept drugs and illegal aliens

- Serve as public information specialists

- Take snow surveys and control avalanches

- Do archaeology, geology and paleontology

- Map caves and abandoned mine shafts

- Document historical buildings and cultural landscapes

- Administer cemeteries, memorials, and shrines

- Issue filming permits and utility right-of-ways

- Monitor marine debris and survey for fish

- Collect fees and operate entrance stations

- Manage campgrounds and visitor centers

- Oversee oil, gas, and mineral operations

- Produce living history demonstrations

- Curate museums and maintain archives

- Combat night sky and noise pollution

- Manage wildfires and scenic rivers (Source: Charles R. “Butch” Farabee, Jr., National Park Ranger: An American Icon)

Take A Deeper Dive

I recommend the following books:

- The Birth of the National Park Service by Horace Albright

- Oh Ranger by Horace Albright

- Hey Ranger by Jim Burnett

- Ranger Confidential by Andrea Lankford

- The Wonder of It All: 100 Stories from The National Park Service by The Yosemite Conservancy

About The People Behind More Than Just Parks

You should probably know that we don’t just make this stuff up out of thin air. My sons have spent their entire adult lives exploring and filming America’s national parks and public lands.

As for me, I’m a retired lifelong educator and a proud dad of these two wonderful guys who are hopelessly obsessed with the national parks. I taught history for over a quarter of a century. Now I enjoy researching and writing articles for More Than Just Parks. I’m always on the hunt for topics where nature and history intersect so please feel free to share any ideas that you might have with me.

We’ve worked with the National Park Service, the Department of Interior, and the U.S. Forest Service for years creating films on important places and issues. Our work has been featured in leading publications all over the world and even some people outside of our immediate family call us experts on the national parks.

Meet The Parks Brothers

We’re Jim Pattiz and Will Pattiz, collectively known as the Pattiz Brothers (and sometimes the Parks Brothers) and we absolutely LOVE the national parks.

Our goal here at More Than Just Parks is to share the beauty of America’s national parks and public lands through stunning short films in an effort to get Americans and the world to see the true value in land conservation.

We hope you’ll follow our journey through the parks and help us to keep them the incredible places that they are. If you’re interested in joining the adventure then please sign up below!

Leave a Reply