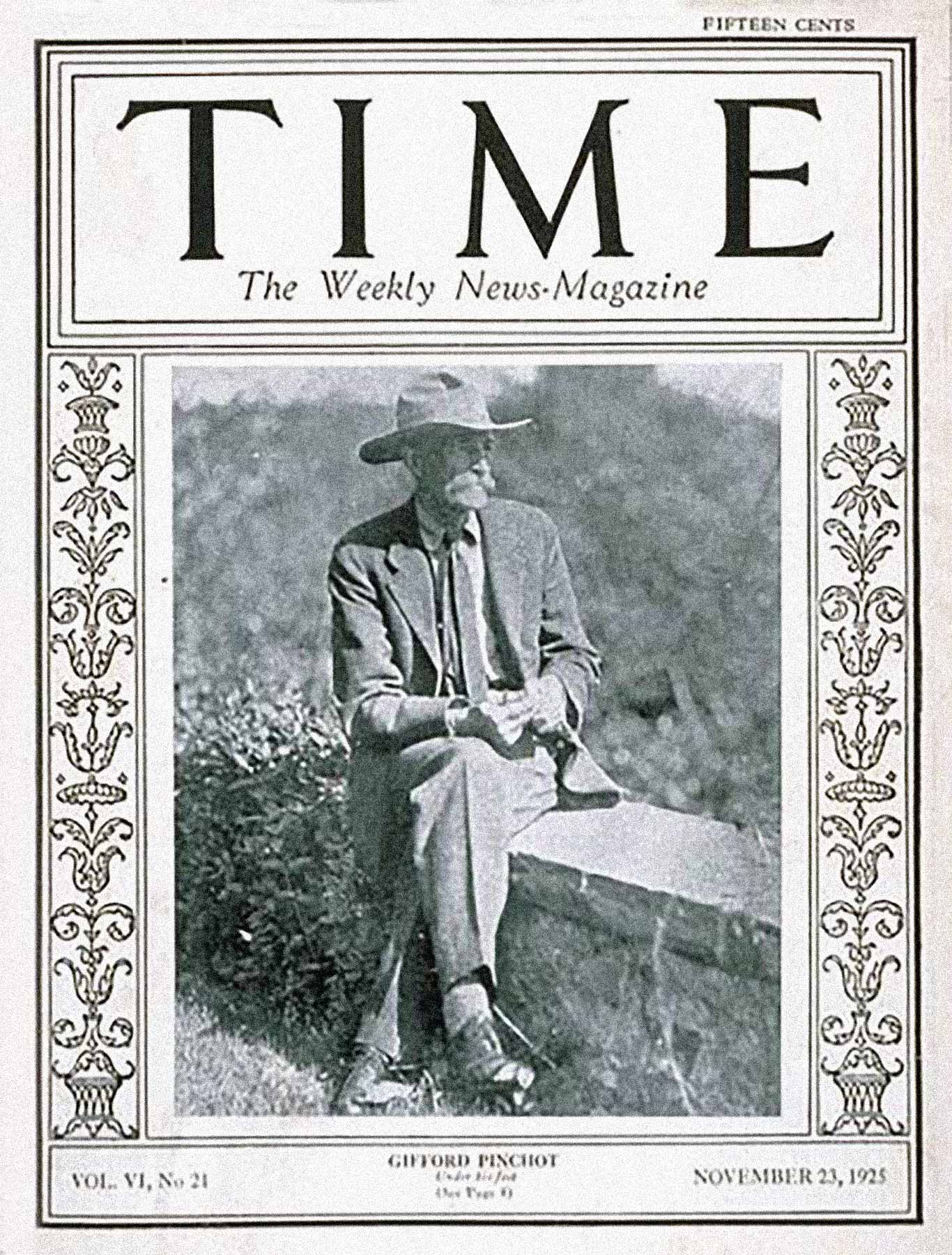

Gifford Pinchot – America’s First Forester

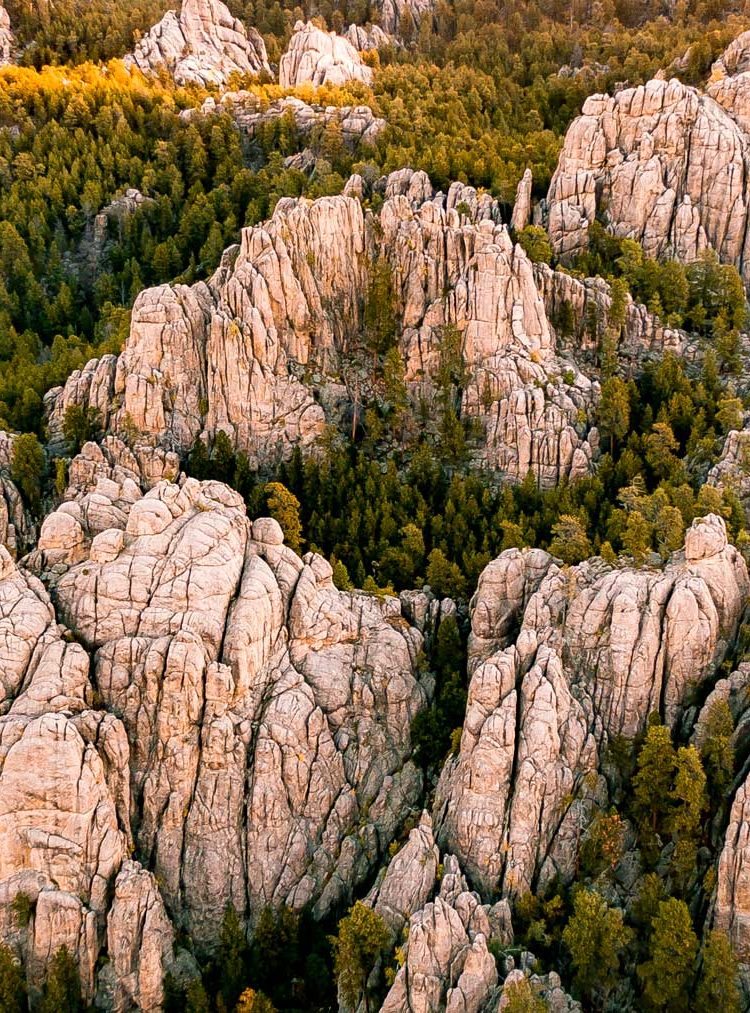

He was America’s first forester. In a time when our nation’s forests were in danger of being decimated, Gifford Pinchot developed a plan to balance their use with their preservation.

His approach became known as “Utilitarian Conservation” whereby natural resources, such as lumber, were to be used in a sustainable manner. Central to this idea was the premise that, for those resources which were being depleted, provisions would have to be made to ensure their replacement.

Ideally, outputs would equal inputs which in turn would create a replaceable supply for generations to come.

As a consequence of his vision and his leadership in the field of conservation and environmentalism, Gifford Pinchot is one of More Than Just Parks environmental heroes.

“Unless we practice conservation, those who come after us will have to pay the price of misery, degradation, and failure for the progress and prosperity of our day.”

-Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot Family

(Courtesy of Wikimedia)

Gifford Pinchot came from two of New York’s wealthiest and most successful families. Descended from French immigrants, the Pinchots settled in Milford, Pennsylvania and quickly became real estate speculators who launched a series of successful entrepreneurial ventures.

His grandfather, Cyrille Pinchot, amassed a fortune as a result of his successful business dealings. The level of financial success he achieved enabled his children to pursue whatever interested them.

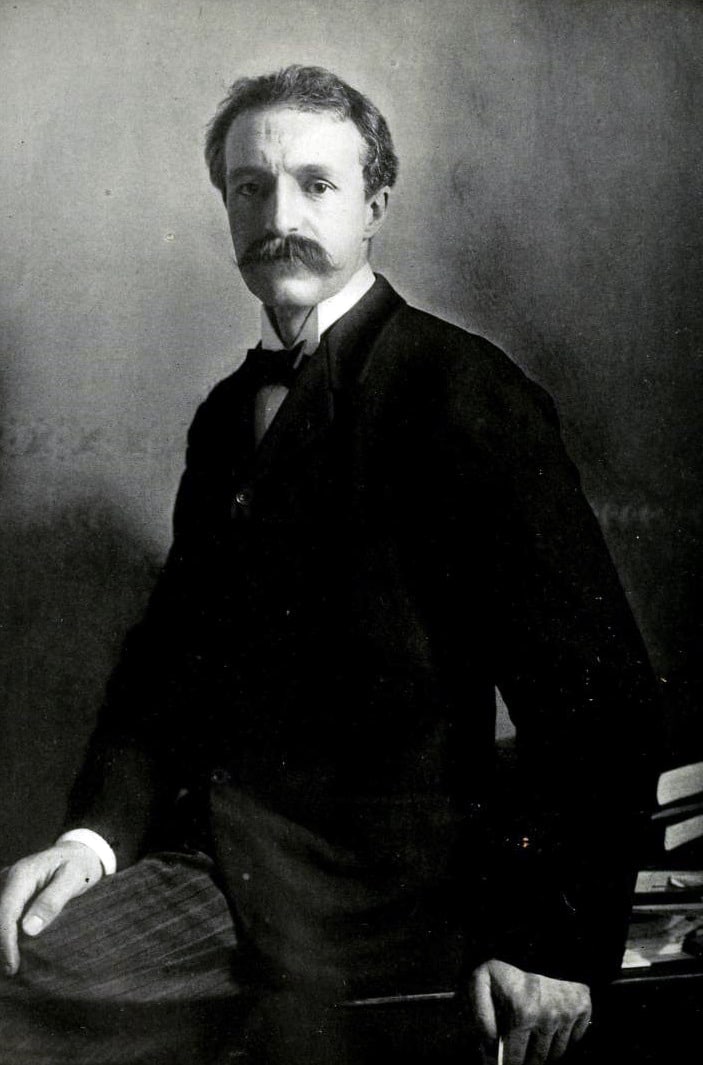

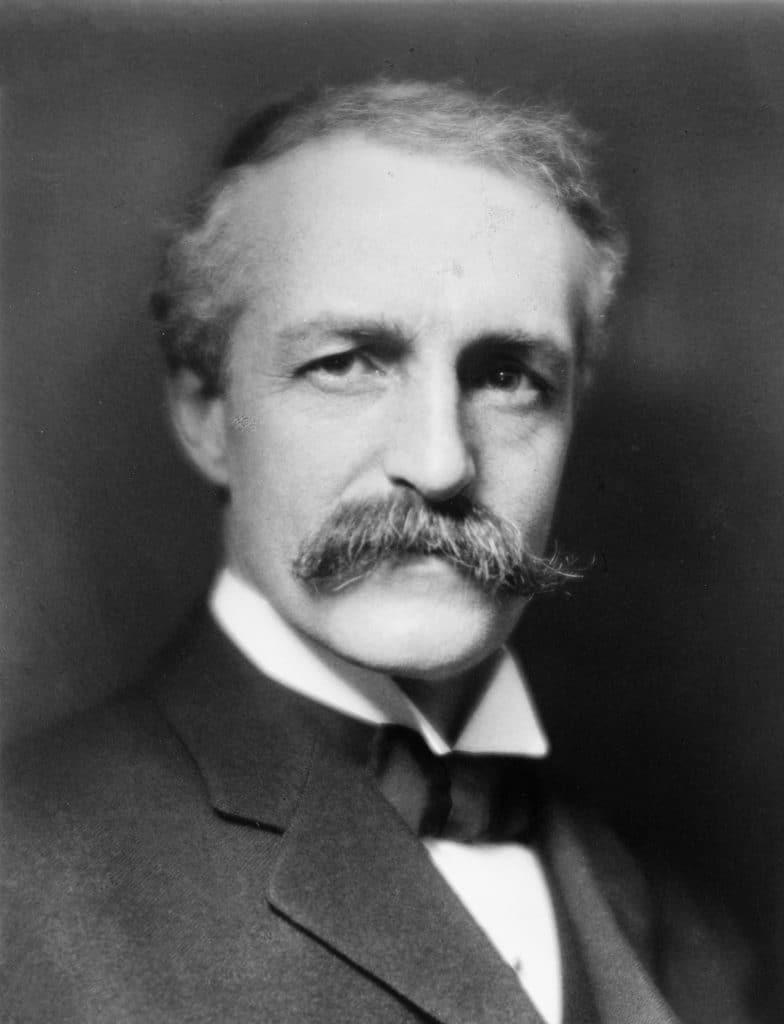

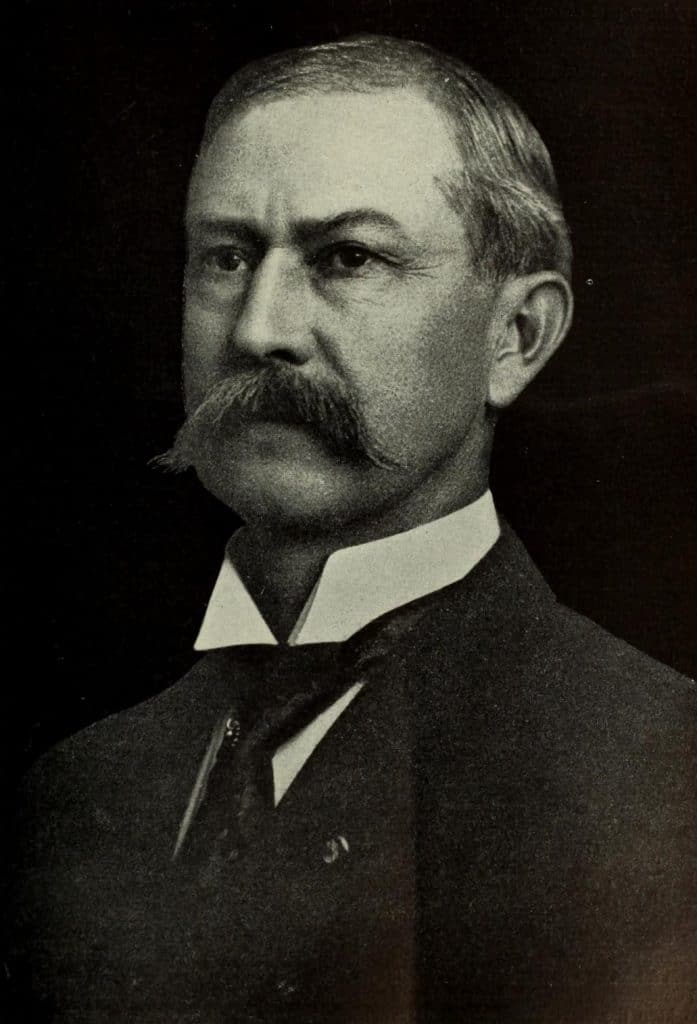

James Pinchot

His son, James Pinchot, who became Gifford’s father, left Milford and moved to New York City. It was there that he became a successful merchant and art collector. His long-term financial success was ensured when he married Mary Eno, Gifford’s mother.

This marriage brought him considerable wealth as her father, Amos Richard Eno, had, like Pinchot’s father Cyrille, built a vast fortune of his own as a merchant and a land speculator.

Planning A Future For Gifford

Given the financial success of the Pinchot and Eno families, James Pinchot was able to retire shortly after his oldest son’s birth in 1865. James then turned his attention to planning a future for young Gifford.

Unlike himself, however, he wanted his son to build a name for himself as someone who would make a difference, not for his family, but for his country.

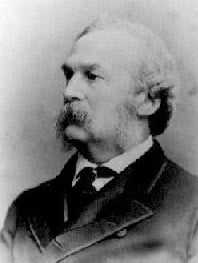

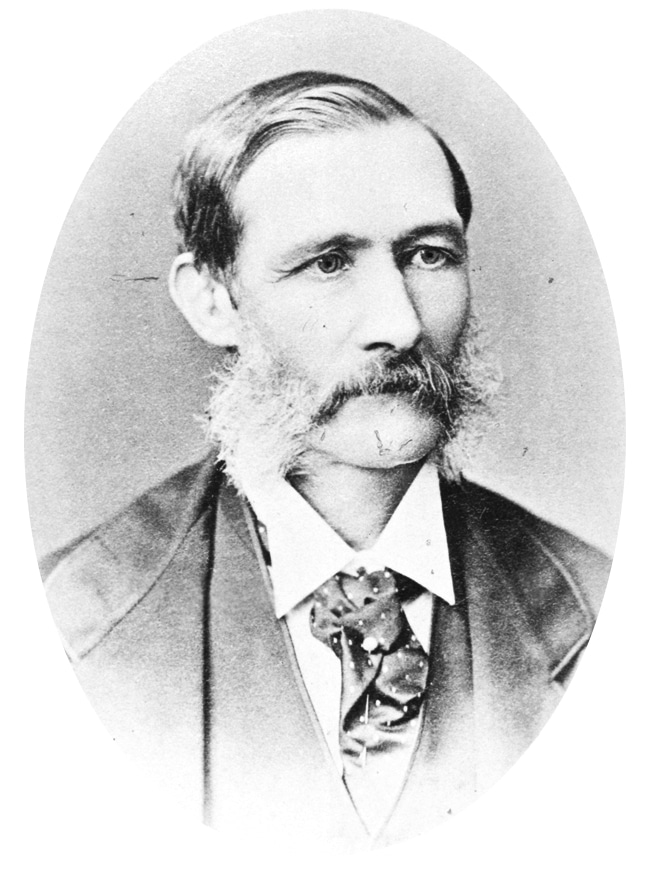

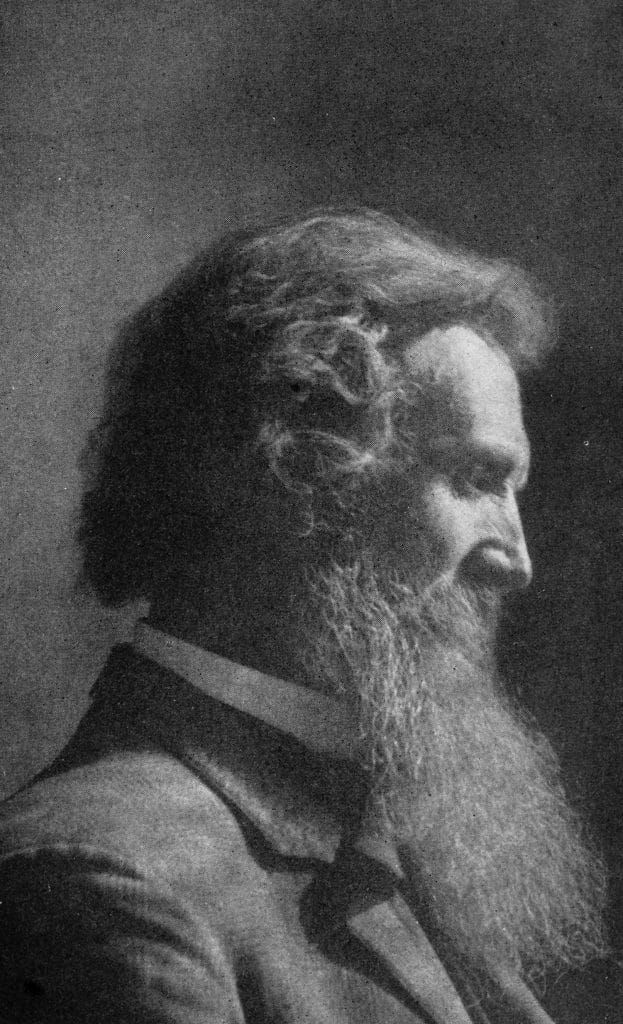

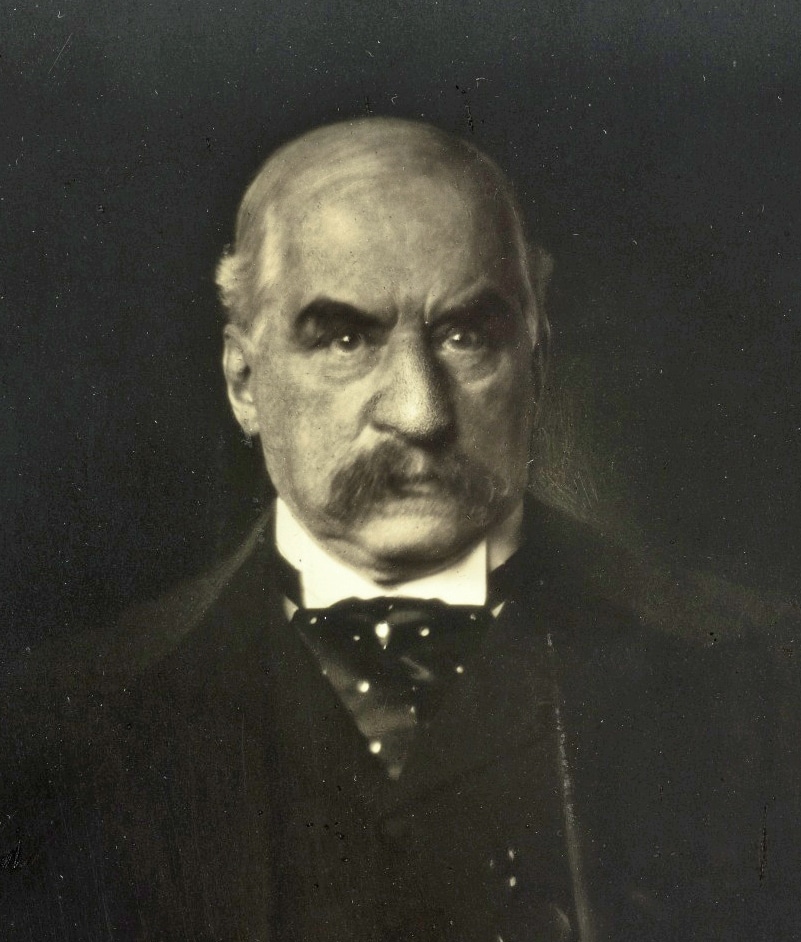

George Perkins Marsh

In considering a future for the eldest child, James and Mary Pinchot were deeply influenced by the writings of George Perkins Marsh. Marsh was the first environmental leader to challenge the idea that human activity is always beneficial to the environment.

Through his groundbreaking work, Man and Nature, first published in 1864, Marsh wrote that humankind could destroy itself if it did not protect its natural resources and pursue sustainable growth strategies instead.

RELATED: George Perkins Marsh-The Father Of Climate Change

“At a time when the United States was moving at breakneck speed to industrialize and develop the national economy by exploiting its wealth and natural resources to the fullest, Marsh’s was a lonely voice cautioning against the risks of careless growth.”

-David Lowenthal, George Perkins Marsh: Prophet of Conservation

A Future In Forestry

As Char Miller writes in his biography of Gifford Pinchot, “Before he entered Yale College as a member of the class of 1889, his father had reportedly popped a question that would change his life. How would you like to be a forester?

This was, Gifford would remember, an amazing question for that day and generation–how amazing I didn’t begin to understand at the time.”

“He did not because, George Perkins Marsh’s influential book notwithstanding, no American had yet accepted its practical consequence–making forestry a career.” (Source: Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism, by Char Miller)

“The vast possibilities of our great future will become realities only if we make ourselves responsible for that future.”

-Gifford Pinchot

Studying Forestry Abroad | A Young Man In A Hurry

(Courtesy of Wikimedia)

When Gifford Pinchot attended Yale, there was no science of forestry offered there or anywhere else in America. Pinchot was told by Dr. George Loring, former Secretary of the Department of Agriculture, that there was little opportunity for him as the field he was proposing to pursue simply did not exist.

From our vantage point today, it’s difficult to imagine that a nation as powerful and prosperous as the United States of America did not offer any training in how to maintain and preserve some of its most precious resources.

This was the reality which Gifford Pinchot confronted in the 1880s.

Setting Sail For Europe

Fortunately for America, Pinchot possessed both the financial resources and the personal drive necessary to defy the odds. In the fall of 1889, after graduating from Yale, he set sail for Europe to begin training for his life’s vocation.

In Europe, there was no shortage of places to learn his craft. The challenge for Pinchot was to decide who could offer him the best possible education in the shortest allowable time.

Forest As A Crop

As a young man, Gifford Pinchot already understood that he wanted to return to America in a position to be considered an “expert” when it came to the science of forestry. To increase his knowledge and understanding, he enrolled in courses at the L’Ecole Nationale Forestiere (the National School of Waters and Forests).

It was there that he was first taught to think of a forest as a “crop,” which needed to be harvested and replanted.

In the French system, foresters were trained to ensure the nation maintained its forests through policies placing limits on what could be cut down while ensuring the planting of replacement trees.

It was only in this way that the nation’s forests would not be decimated by its timber industries.

Dietrich Brandis

Pinchot’s teachers, foremost among them Dietrich Brandis, taught him about the importance of what was called a “stocked forest.” This simply meant the cutting of trees did not exceed their replanting.

Brandis was a German botanist and forestry expert. He had served with the British Imperial Forestry Service in India for thirty years. It was there where he acquired extensive practical experience.

Frederick Law Olmstead & The Biltmore Estate

Pinchot’s future as a forester would be shaped by the influences in his life. At each stop along the way, he found at least one mentor/teacher who helped him to develop his craft. In Europe, it was Dietrich Brandis.

When he returned to America, Pinchot’s first opportunity to put the ideas he had learned from him into practice came when he was hired as the forester for George Vanderbilt’s fabulous Biltmore Estate.

(Courtesy of Wikimedia)

Vanderbilt had also commissioned the famed landscape artist Frederick Law Olmstead. Olmstead, who was considered the father of American landscape architecture, was commissioned to create a harmonious relationship between man and nature.

Pinchot became Olmstead’s assistant. He learned how to combine forestry and artistry.

Vanderbilt’s estate became a “learning laboratory” for Gifford Pinchot. He was able to apply his ideas, determine which ones worked and which ones didn’t, before moving on to serve as the 4th Chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry.

“Pinchot had an ambition to change the world. That ambition drove him to soak up as much as possible from older experts, and then diverge from those perspectives.”

–Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot and the Creation of America’s Public Lands, by John Clayton

Gifford Pinchot Goes To Washington

For a man whose ambition knew no limits and who was determined to reshape forestry in America, it was time to take what he had learned and move on to Washington. It would not be Pinchot’s knowledge of the science of forestry, which he himself would admit was limited, but his ability to play the political game that enabled him to attain his goals.

James Pinchot had turned his New York home into a meeting place where powerful people came to wine and dine. His political connections in Republican circles proved helpful to his son who was already establishing a reputation as a renown expert in the field of forestry.

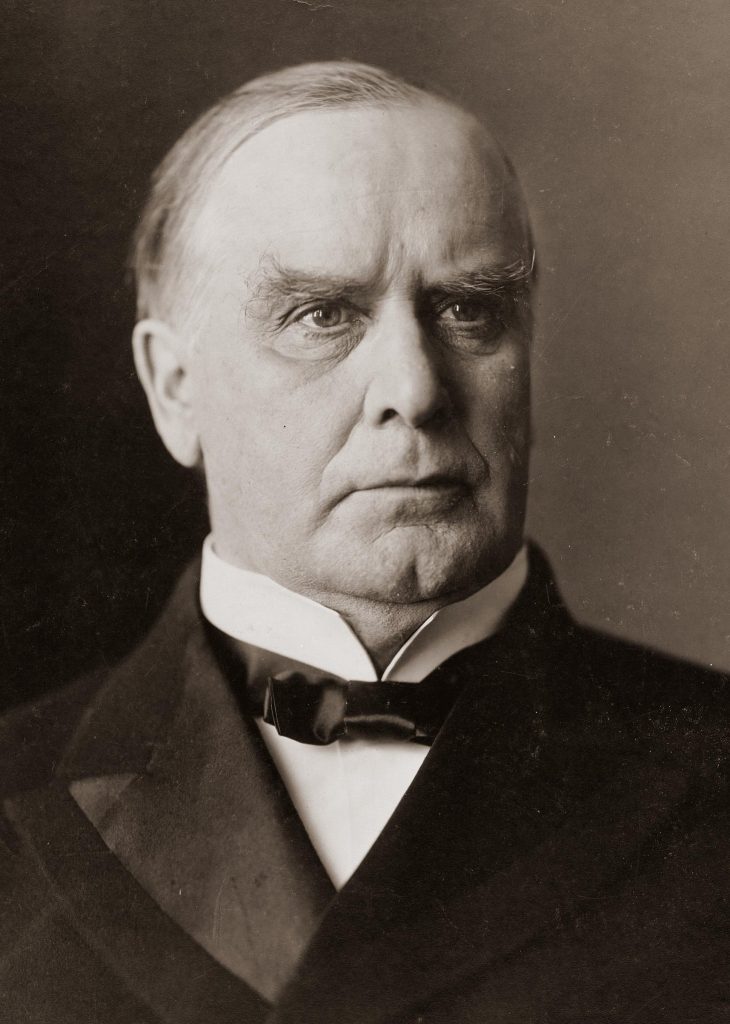

In 1898, Republican President William McKinley tapped that expertise by appointing Pinchot as the 4th head of the Division of Forestry.

“Where conflicting interests must be reconciled, the question shall always be answered from the standpoint of the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run.”

-Gifford Pinchot

Theodore Roosevelt & Gifford Pinchot | A Conservation Friendship

Gifford Pinchot and Theodore Roosevelt forged a friendship before TR’s presidency. Both were New Yorkers. Pinchot visited Roosevelt while he served as governor of the state.

The two men engaged in boxing and wrestling matches. A friendship developed between them as they shared their love of the outdoors.

“He and the president seemed of like minds, especially on matters of federal conservation policy. As with many of their generation, they were appalled by the human destruction of nature everywhere visible in early twentieth-century America. The solution, they believed, lay in federal regulation of the public lands and, where appropriate, scientific management of these lands natural resources.”

–Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism, by Char Miller

When William McKinley was assassinated in 1901, Roosevelt became president. Like Pinchot, the new president believed the nation’s forests should be transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture where they could be more effectively managed.

He also shared Pinchot’s dream of creating a “Forest Service” comprised of professionals who would ensure the proper management of these important public lands.

Roosevelt used his power as president to persuade Congress to authorize the transfer and support the creation of the U.S. Forest Service in 1905.

The U.S. Forest Service

Gifford Pinchot was named by Theodore Roosevelt to lead the newly created U.S. Forest Service. Pinchot had witnessed firsthand how political patronage could undermine an agency’s effectiveness.

One of his first actions was to mandate competitive civil service examinations to ensure that the nation’s foresters were qualified professionals.

He also created a decentralized administrative structure whereby power and autonomy flowed to the people in the field who were most familiar with the challenges and opportunities existing in different parts of the country.

Pinchot had also become a skilled politician in his own right. He understood that by setting up these offices where the forests were located and embedding them within the local communities, they would be able to build political support within those communities.

RELATED: Meet The Real Life Batman & Robin Of The National Parks (unmasking included)

He also understood the importance of public relations. As Char Miller notes:

“The Forest Service set up an in-house press bureau and made great use of a new technological marvel: a mailing-label machine that could rapidly crank out the 670,000 addresses of groups and individuals targeted by the service to receive its reports and releases.“

John Muir & Gifford Pinchot | Another Conservation Friendship

(Courtesy of Wikimedia)

How to describe John Muir? A Scottish-American naturalist? A philosopher? A writer? Muir was all of this and much more. He has been called “John of the Mountains.”

He has also been called the “father of the national parks.” Through his deeds and his words, John Muir brought the beauty and majesty of nature to life for the people of his time. And he fought to preserve these natural wonders.

RELATED: 10+ AMAZING John Muir Facts

“The most prominent preservationist spokesman was John Muir. Inspired by the magnificence of Yosemite and informed by his own natural mysticism, Muir spearheaded the crusade to conserve the natural world in part for its own sake, and not solely for man’s.

Curt Meine, Aldo Leopold His Life And Work

In his passionate regard for all things wild, Muir tapped into powerful sentiments that the practical business of nation-building had all but buried. In Muir’s view, no conceivable use of a 3,000 year old sequoia or a unique mountain valley could possibly be wiser than the act of letting them be.”

Through his impressive body of work, John Muir continues to be recognized as one of the leaders of the school of conservation which considered preservation to be the highest possible good.

Muir and Pinchot have been depicted as rivals who battled over what it truly means to be a conservationist.

In reality, Muir and Pinchot were friends for much of their adult lives until a disagreement over the Hetch Hethcy Valley (see next section) led to dissolution of that friendship.

“In some circles, Pinchot is also famous as a counterpoint to Muir. Many historians use the two men to embody opposing philosophies. The romantic Muir is preservation: leaving nature alone so as to benefit from its holistic wonder. The practical Pinchot is conservation: using natural resources sustainably to serve what Pinchot called the ‘greatest good for the greatest number in the long run.’

–Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot and the Creation of America’s Public Lands, by John Clayton

To regular folks, preservation and conservation may seem like similar ideas, especially in contrast to the wanton exploitation of natural resources for short-term gain. But to some scholars, the difference between these near-synonyms helps explain America’s twentieth-century environmental history.”

Muir Supported Pinchot’s Career

John Muir was a guest at the home of James and Mary Pinchot. It was there that he began a friendship with a young Gifford Pinchot. Like Dietrich Brandis, Frederick Law Olmstead, and Theodore Roosevelt, Muir became one of those men who influenced Pinchot and helped him to pursue his dream of becoming America’s first forester.

The battle over Hetch Hetchy would pit the two against each other. Muir understood the need for public use of public lands just as Pinchot understood the importance of preserving and protecting those lands against their exploitation.

While the two men have been cast as opposites on the conservation spectrum, Muir actually championed Pinchot’s career believing that he would provide the necessary balance between preservation and use of America’s public lands.

Hetch Hetchy

The battle over Hetch Hetchy was a fight to determine whether a beautiful valley would remain in its natural state or serve the growing city of San Francisco’s water needs. The larger issues at stake would frame environmental debates for years to come.

The fundamental issue involved two concepts. The first is preservation. Should nature be left alone so that people can enjoy its primal wonders? The second is conservation. Should natural resources be used to serve the greatest good for the greatest number?

RELATED: HETCH HETCHY: The Epic Environmental Battle That Changed America

The Greatest Good For The Greatest Number

In his congressional testimony, Pinchot argued in favor of building the dam. He said, “So we come now face to face with the perfectly clean question of what is the best use to which this water that flows out of the Sierras can be put.

As we all know, there is no use of water that is higher than the domestic use. . . .We come straight to the question of whether the advantage of leaving this valley in a state of nature is greater than the advantage of using it for the benefit of the city of San Francisco.”

Pinchot went on to argue that applying the principle of the “greatest good for the greatest number,” the benefits accrued to the people of San Francisco from having the dam far outweighed leaving the valley in its current state of nature.

The Raker Bill

It would be Congress that would decide the fate of the Hetchy Hetchy Valley. California Rep. John E. Raker submitted a bill granting the city of San Francisco the right to dam the Hetchy Hetchy Valley as a reservoir and also providing the city the right of municipalized electricity as well.

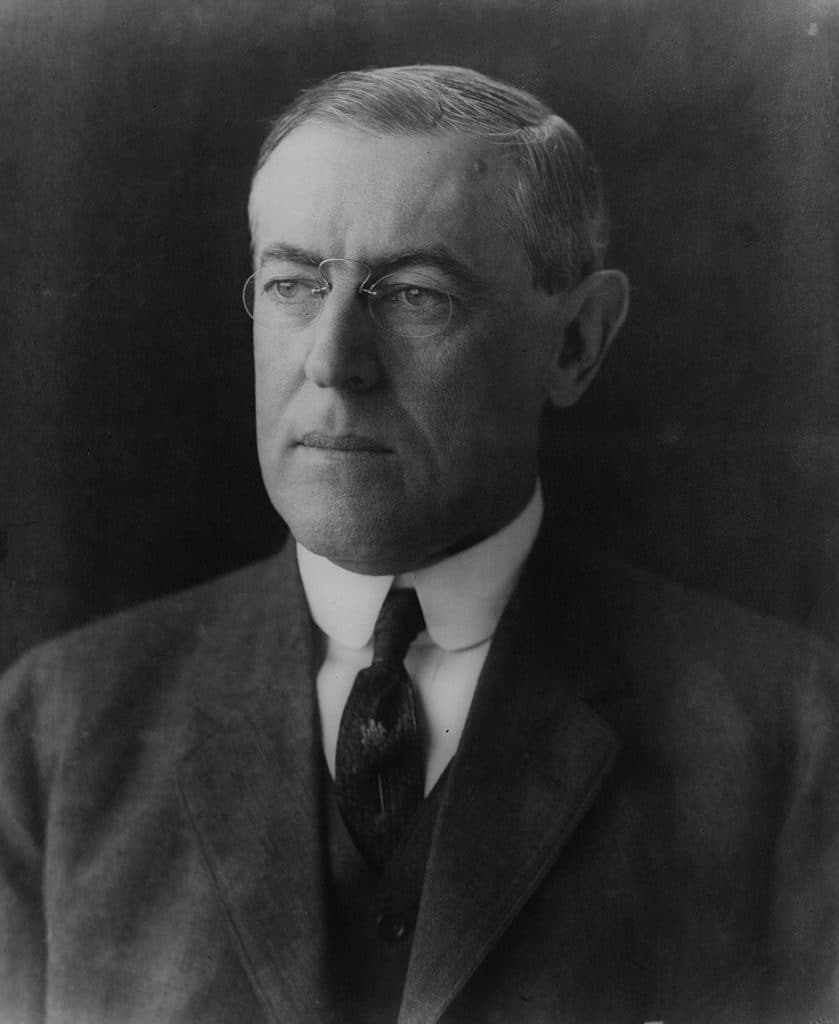

The bill passed both houses of Congress. It became known as the Raker Act. It was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 19, 1913.

The Ballinger Pinchot Controversy

The Ballinger-Pinchot Controversy would have wide ranging consequences for Theodore Roosevelt’s successor, William Howard Taft, and the Republican Party which he led.

The controversy arose when Gifford Pinchot became convinced that the Secretary of the Interior, Richard Ballinger, was supporting private trusts in the handling of water power issues.

At issue was a series of coal claim purchases made by Clarence Cunningham of Idaho. Cunningham was granted certain claims to mine coal in Alaska.

The Alaska Syndicate

It was then discovered that Cunningham was actually acting on behalf of an “Alaska Syndicate” operated by J.P. Morgan and Issac Guggenheim. Both men were powerful financiers.

This was a violation of then existing laws. Pinchot was concerned that Ballinger was obstructing the investigation. He also feared that President Taft had renounced his predecessor’s commitment to conservation.

Pinchot responded by sending a letter to Senator Jonathan P. Dolliver which was read on the floor of Congress and entered into the Congressional Record. The letter, critical of Taft’s leadership in the matter, led him to fire Pinchot in January of 1910.

Split In The Republican Party

The Ballinger-Pinchot Controversy widened the growing rift in the Republican Party between those who supported the ideals of Theodore Roosevelt and those whose loyalty was to William Howard Taft.

(Courtesy of Wikimedia)

Ballinger had sought to make public resources more available for private exploitation. As a consequence of Pinchot’s firing and the growing dissension within the Republican Party, Ballinger was forced to resign on March 12, 1911.

The damage proved irreversible. Theodore Roosevelt challenged William Howard Taft for the Republican Party nomination in 1912. Denied the nomination by the party bosses, Roosevelt ran instead as an Independent and a leader of the Bull Moose Party.

The battle between these two men split Republicans resulting in the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

During his unsuccessful campaign, Gifford Pinchot served as one of Theodore Roosevelt’s closest political advisors writing many of his speeches.

RELATED: No, Theodore Roosevelt Was Not The Greatest Conservation President. It was Jimmy Carter.

Life After Roosevelt | The Rise Of A Political Progressive

After the 1912 campaign, Gifford Pinchot continued to pursue conservation issues. Ten years after his dismissal from the U.S. Forest Service, he returned to public service. Pennsylvania Governor William Sproul appointed him as head of Pennsylvania’s forestry division.

Two years later, he succeeded Sproul by winning the Republican nomination as governor. He was elected and served a four year term during which time he became a progressive political crusader siding with labor over management.

He went further than any of his predecessors by preventing mine operators from deploying a private police force to break up a strike.

“The need to link present-day policy to future needs, a staple of conservationist argument since at least the writings of George Perkins Marsh in the mid nineteenth century, informed Pinchot’s categorical rejection of what he called a ‘stupidly false’ term–inexhaustible resources.

–Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism, by Char Miller

Neither coal, wood, soil, forage plants, nor water was infinite; each was at the mercy of unrestrained economic forces seeking short-term profit at the expense of long-term sustainability.

Only strict regulation could alter these dangerous consumption patterns, he contended, an argument that was central to his abiding faith. ‘The conservation of natural resources is the basis, and the only permanent basis, of national success.'”

A “New Deal” For The People Of Pennsylvania

Under Pennsylvania law, Pinchot could not succeed himself as governor. He was, however, able to run again in 1930. He did so and was elected for a second time.

The national landscape had changed significantly since his first term with the advent of the Great Depression. Governor Pinchot experimented with state intervention in the development of social and economic policy to help struggling Pennsylvanians.

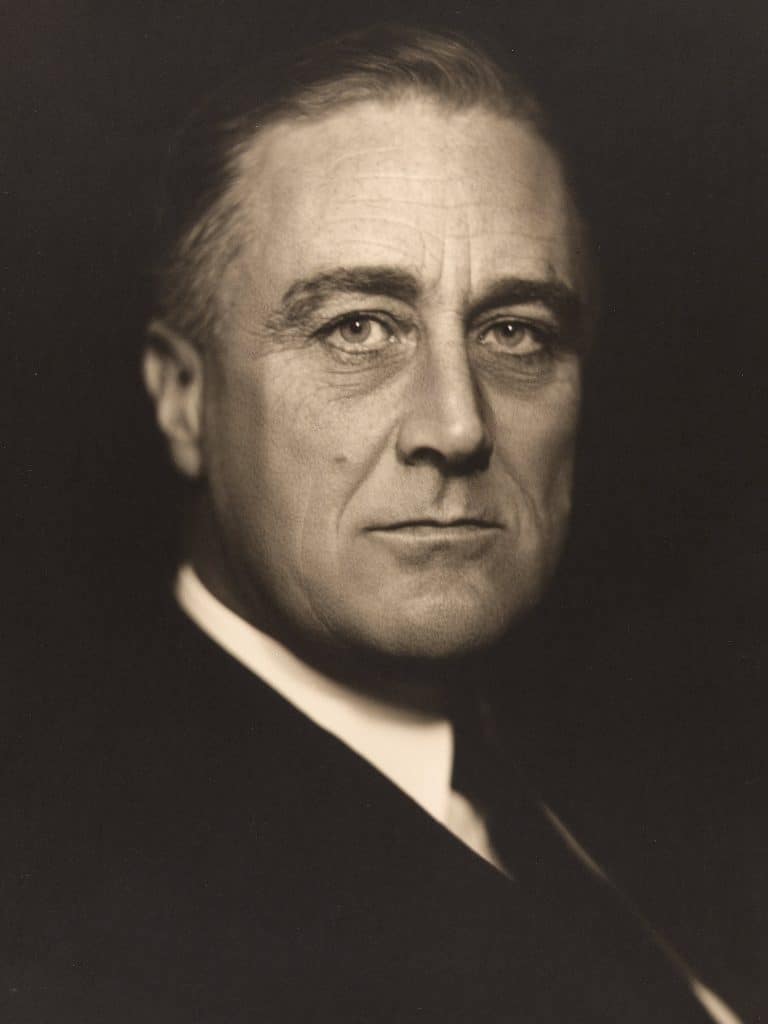

His policies, such as unemployment relief and workers’ compensation were similar to those of New York’s Governor Franklin Roosevelt.

Pinchot went a step farther, however, setting up relief camps across the state. Thousands of unemployed Pennsylvanians were given the opportunity to upgrade roads and public lands. His efforts became the model for President Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps.

RELATED: The First Green New Deal Happened Nearly 100 Years Ago. What Happened?

The Training Of A Forester

President-elect Franklin Roosevelt reached out to Gifford Pinchot in 1932 asking his advice on how the new administration could apply its conservation efforts to America’s public lands.

Pinchot responded by encouraging the new president to have the federal government take control of millions of additional acres of public lands and ensure their protection for generations yet to come.

“What would happen, for instance, if the definition of the greatest good change over time, a shift in part dictated by what the greatest number construed as good? That question is decidedly political, and it is no surprise that Pinchot, who throughout his career had been alert to new currents in scientific scholarship and public activism, responded once more.”

–Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism, by Char Miller

After he left office, Pinchot dedicated himself to revising his 1917 publication, The Training of a Forester. As our understanding of our impact on the environment grew, Pinchot increasingly advocated that applying the “greatest good for the greatest number” meant finding a middle ground between utilitarian conservation and a more preservationist approach.

The Legacy Of Gifford Pinchot

When Gifford Pinchot set sail for Europe after graduating from Yale, America had no school of forestry. Our nation’s forests were in danger of being decimated by private interests who thought only of the money to be made at the time. Our public lands were in jeopardy.

Pinchot changed that. As America’s first forester, he helped create a service dedicated to the scientific management of our nation’s forest lands.

Working with Theodore Roosevelt, he helped to establish the U.S. Forest Service, served as its first leader, and professionalized the ranks of those tasked with the management of these important public lands.

“The vast possibilities of our great future will become realities only if we make ourselves responsible for that future.”

-Gifford Pinchot

It’s Still The Greatest Good For The Greatest Number

Pinchot’s critics contend he was too quick to stress the “use” of America’s public lands as in the case of Hetch Hetchy.

What these critics ignore is that this was the same man who took on the Secretary of the Interior and President of the United States when he believed our nation’s public lands were being exploited for private gain.

Gifford Pinchot passed away in 1946. Had he lived longer, it’s likely that his conservationist ethic would continue to be guided by the greatest good for the greatest number.

What would have changed was how he interpreted that “greatest good.”

RELATED: A Woman Started The Modern Environmental Movement. Can It Continue?

“When the facts change, I change my mind.”

-John Maynard Keynes

Just as he embraced innovative solutions to tackling the Great Depression, such as unemployment insurance and workman’s compensation, Gifford Pinchot likely would have embraced the environmental movement and the science of a changing climate.

Through Pinchot’s example we are reminded that it takes dedicated public servants, who are willing to put the well being of their country first and foremost, to ensure a sustainable future.

He also reminds us that, ultimately, it takes a dedicated citizenry to hold their elected officials accountable.

“In The Use of the National Forests, a 1907 Forest Service publication, the then-chief [Pinchot] had asserted that the public forests ‘exist to-day because the people want them.

–Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism, by Char Miller

To make them accomplish the most good the people themselves must make clear how they want them run.'”

To Learn More:

- Clayton, John. Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands, Pegasus Books, 2019.

- Meine, Curt. Aldo Leopold: His Life And Work, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1988.

- Miller, Char. Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism, Island Press, 2001.

- Righter, Robert W. The Battle Over Hetch Hetchy: America’s Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism, Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Wolfe, Linnie Marsh. Son of the Wilderness: The Life of John Muir, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1945.

- Worster, Donald. A Passion of Nature: The Life of John Muir, Oxford University Press, 2008.

People in general have forgotten why the National Forest System was designed to do in the first place. They were supposed to managed for “greatest good for the greatest number of people.’ Our National Forest System were meant to be managed as a working forest that meets everyone’s needs not just one or two competing interests.