Hetch Hetchy was the first major battle of the environmental movement. It pitted a powerful city against a dedicated group of conservationists. It pitted Gifford Pinchot, America’s first forester, against John Muir, America’s legendary conservationist.

This fight set the stage for future battles between those who believed natural resources were to be used for the greatest good versus those who believed natural resources were to be preserved for the greatest enjoyment.

Hetch Hetchy is the incredible story of America’s most controversial dam and the birth of the environmental movement. It is part of our More than Just Parks Environmental Heroes series.

Hetch Hetchy: A Battle of Use vs Preservation

The battle over Hetch Hetchy was a fight to determine whether a beautiful valley would remain in its natural state or service the growing city of San Francisco’s water needs. The larger issues at stake would frame environmental debates for years to come.

The fundamental issue involved two concepts. The first is utilitarian conservation. Should natural resources be used to serve the greatest good for the greatest number?

“Historians of the American conservation movement regard Pinchot as the foremost exemplar of the utilitarian approach to conservation, according to which man has a right to use natural resources, but also an obligation to use them wisely and efficiently–or as the classic criterion put it, ‘the greatest good for the greatest number over the long run.’

-Curt Meine, Aldo Leopold: His Life And Work

As applied to forests and espoused by Pinchot, this meant that the nation’s forest reserves ought not to be maintained as ‘inviolate sanctuaries,’ but opened to enlightened management.”

A Question of Preservation

The second concept is preservation. Should nature be left alone so that flora and fauna flourish while people enjoy its primal wonders?

“In contrast to the utilitarian view, the preservationist approach denied the assumption that the natural world existed solely to serve man’s purposes. Forests might provide for the material well-being of human beings, but they did not exist for this reason alone.

-Curt Meine, Aldo Leopold: His Life And Work

As surely as forests provided timber, so did they provide beauty, inspiration, and the renewal of over-citified spirits. Furthermore, they provided a place for the wild plants and creatures to live out their own lives, according to their purposes. The most prominent preservationist spokesman was John Muir.”

Unintended Consequences of Hetch Hetchy

There is a third concept, too, though it was little understood at the time. It involved the unintended consequences of efforts to shape the environment to meet human needs.

At the time, neither side understood the long-range consequences of human actions to “manage” the environment.

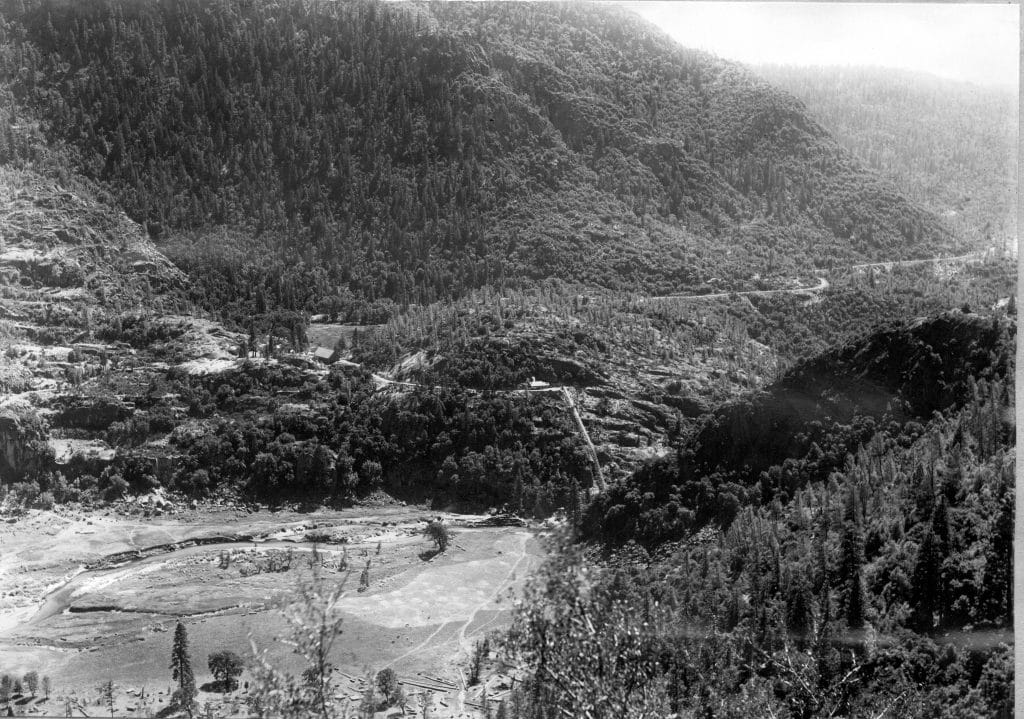

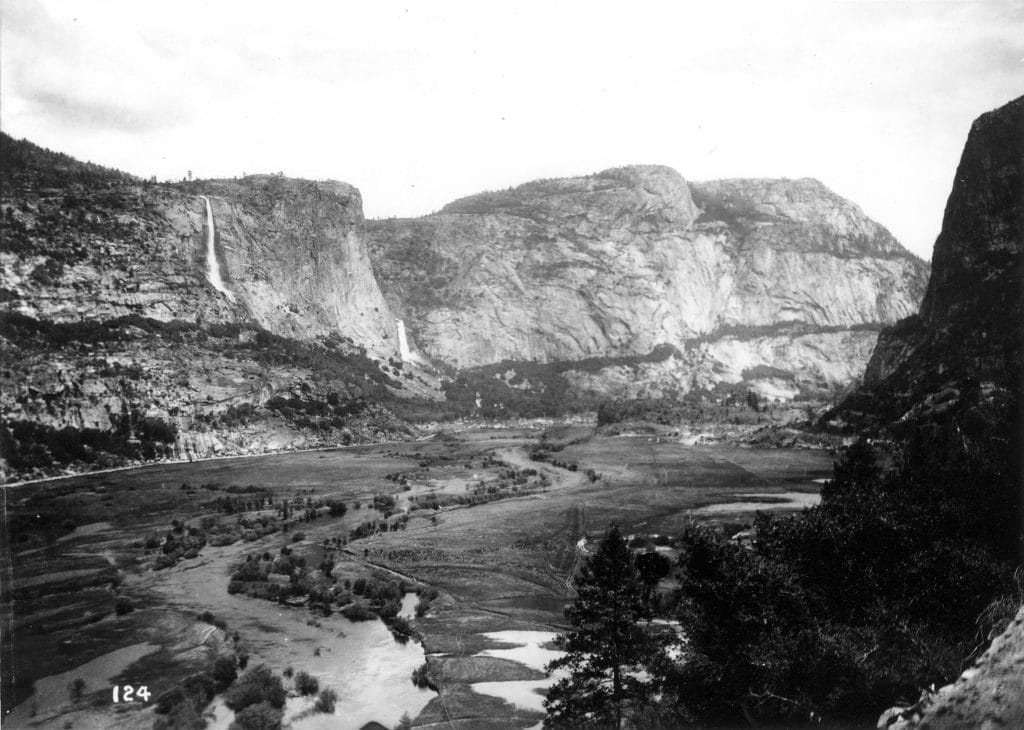

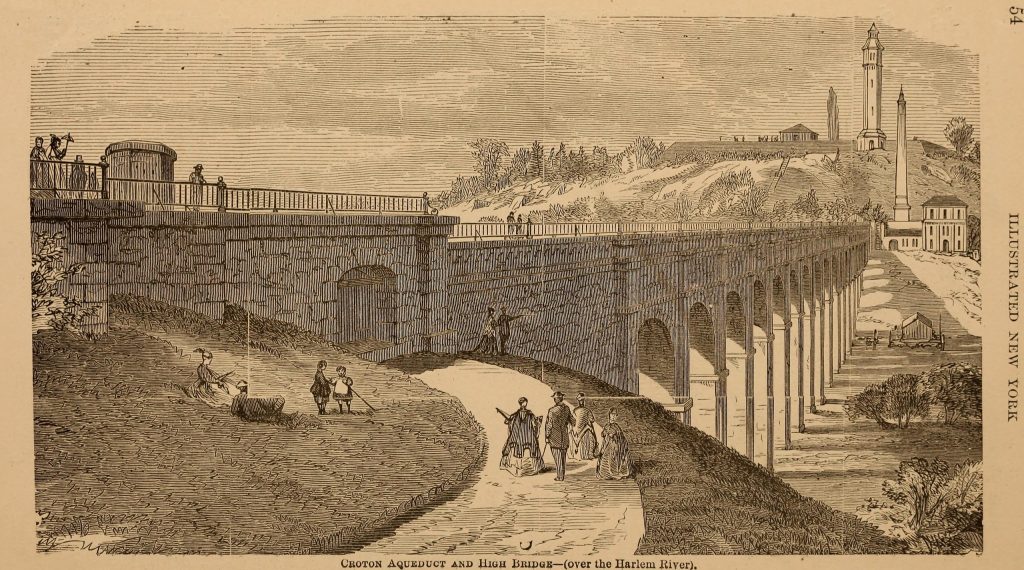

“Congress has set aside the Yosemite Valley as a state park in 1864, established a national park around it in 1890, and then reclaimed the valley as part of the national park in 1903. Now San Francisco wanted to dam one of the two principal watersheds in the park, the Hetch Hetchy valley through which ran the Tuolumne River, to create a reservoir for its water supply.

-Donald Worster, A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir

In the sum of American economic expansion the intrusion might have seemed a minor, obscure matter, but to [John] Muir immense issues were involved: why had the nation preserved that ‘pure wildness’ in the first place? What part should mountains, rivers, natural meadows or wild creatures play in American life?

If the nation set aside some natural places as especially sacred, how far beyond their borders should a sense of the sacred extend? What should be the fate of prairies, wetlands, or coastal marshes? Would there be any room in an acquisitive society for wildness, or for non material spiritual values?”

How Dams Damage Rivers

There are four fundamental ways in which dams damage rivers. First, they block rivers which prevents fish from migrating. This limits their ability to access spawning habitat, seek out food resources, and escape predation.

Second, dams slow rivers. This can be very disorienting to fish and disrupt their migrations as they depend on steady streams and flows to guide them.

Some hydro-power dams withhold and then release water to generate power for peak demand periods, which is particularly disruptive to migrating fish.

Third, dams alter natural habitats and change the ways in which rivers function. Gravel, logs, and other important food and habitat features can become trapped. They also remove water needed for healthy in-stream ecosystems.

Fourth, dams alter water quality. Slow-moving reservoirs heat up, resulting in abnormal temperature fluctuations which can affect sensitive species. This can lead to algal blooms and decreased oxygen levels. (Source: American Rivers, How Dams Damage Rivers)

How Is The Environment Being Impacted

When changes are made there are unintended consequences. As we learned from Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, humankind can damage the environment while attempting to control it. This is why environmental impact statements, which were not required prior to 1969, are so important today.

RELATED: A Woman Started The Environmental Movement (Can It Continue?)

A Local Legend Emerges

The first people, outside of Native Americans, to see the Hetch Hetchy Valley were Joseph, Nate and William Screech in 1850. According to a local legend, Nate spotted a valley to the east that was too far to visit.

On returning home, he asked an Indian chief the name of the valley. The chief replied, “There is no valley. It is only a cut in the hills through which the Tuolumne River runs, but if you think there might be a valley keep looking and if you find such a place I will give it to you.”

Nate went on looking for the valley. He discovered it a few of years later. There, he met the same Indian chief and his wives. The chief began packing up and, when Nate asked him why, he replied, “The valley is yours now.”

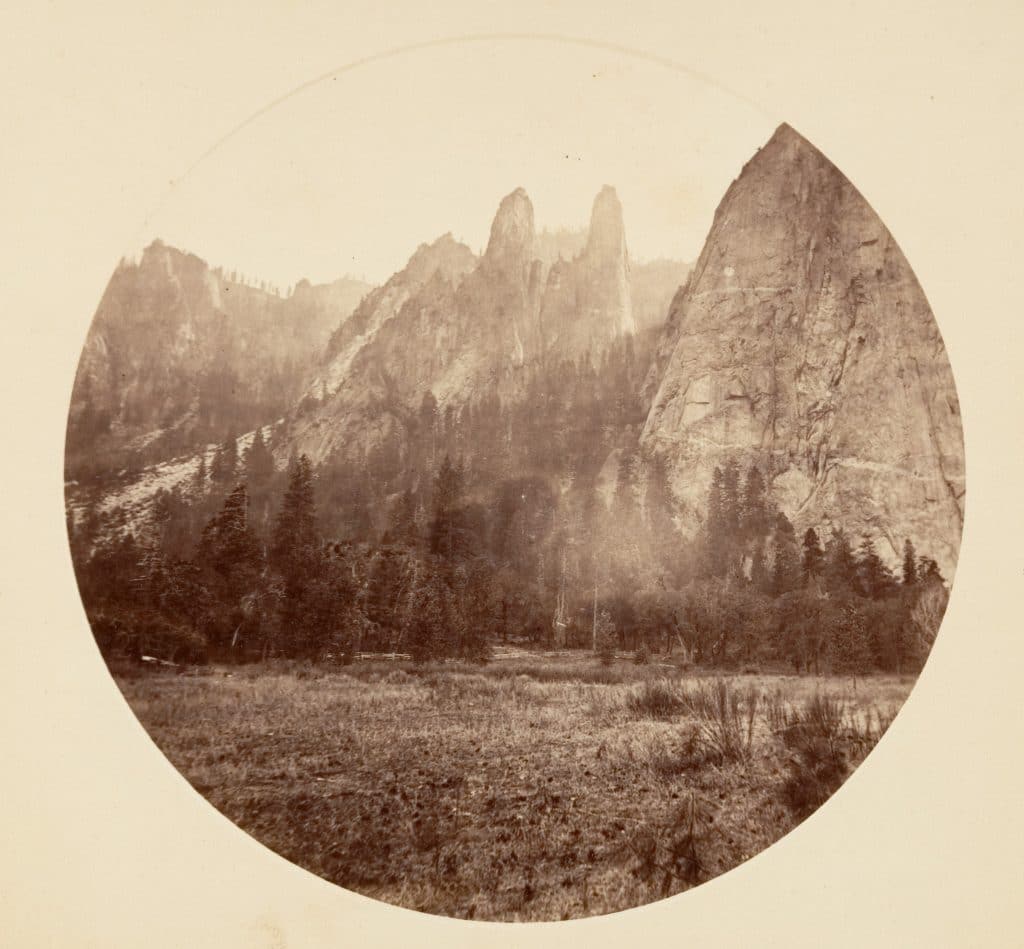

“Far below them, the river cascaded into a peaceful valley floor, a heavenly setting similar to that of the main Yosemite Valley.

-John Clayton, Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands

This valley was isolated and remote, twenty miles northwest of the original. Most people called it ‘Hetch Hetchy,’ a mispronunciation of a Central Mohawk word for a plant that indigenous people were harvesting there when the first white man came along.”

The Hetch Hetchy Valley

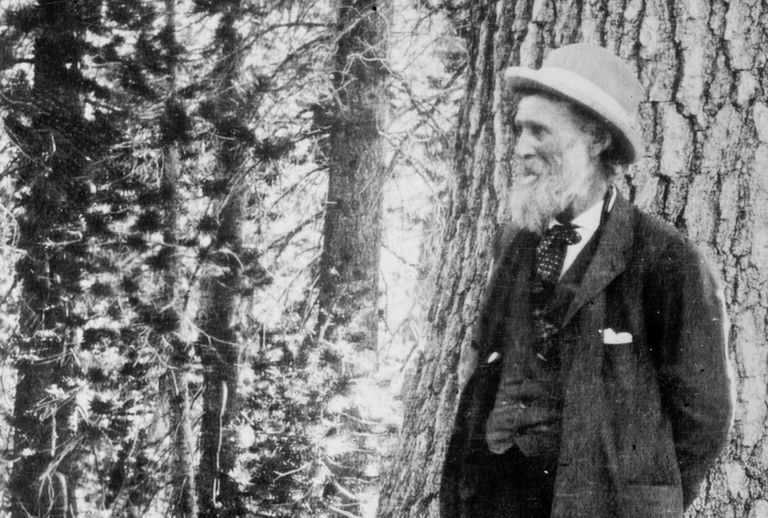

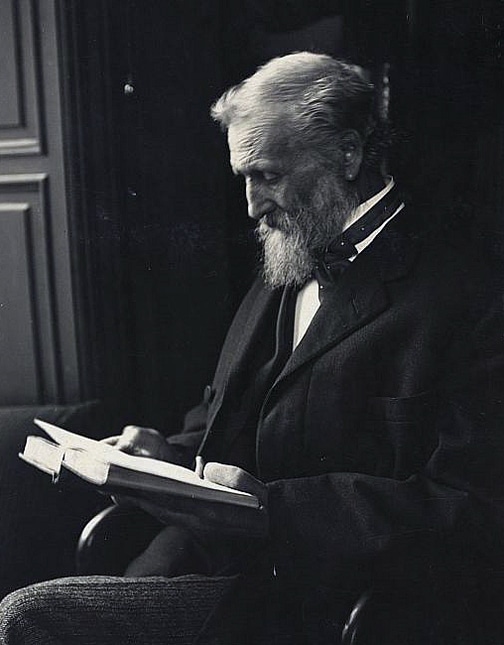

In the autumn of 1871, John Muir visited Hetch Hetchy for the first time. He wrote, “…I have always called it the Tuolumne Yosemite, for it is a wonderfully exact counterpart of the great Yosemite, not only in its crystal river and sublime rocks and waterfalls, but in the gardens, groves, and meadows of its flowery park-like floor.

The walls of both are of gray granite, rise abruptly out of the flowery grass and groves are sculptured in the same style, and in both every rock is a glacial monument.”

(Source: Journal of Sierra Nevada History & Biography, Hetch-Hetchy, Natural History Before The Dam, Joe Medeiros)

“In defense of Hetch Hetchy, Muir crafted some of his most famous prose. Denouncing dam proponents as greedy, he wrote, ‘These temple destroyers, devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature, and instead of lifting their eyes to the God of the Mountains, life them to the Almighty Dollar.

-John Clayton, Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot and the Creation of America’s Public Lands

Dam the Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.'”

RELATED: 10+ AMAZING John Muir Facts

Albert Bierstadt & Hetch Hetchy

Albert Bierstadt was known for his sweeping landscapes of the American West. Like Muir, he was totally transfixed by the Hetch Hetchy Valley. He produced at least four oil paintings of the valley one of which is prominently displayed in Mount Holyoke College’s art museum.

Bierstadt’s paintings and Muir’s writings began to publicize the beauty of the Hetch Hetchy Valley. As a consequence, visitors came to experience it for themselves.

“The landscape painter Bierstadt, who brought his German Romantic training to the valley in 1862, gave the world an even larger portrait, and one in extravagant color, that photographers could not match on any scale.

-Donald Worster, A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir

Over the next decade, he produced fifteen large oils that transformed the valley into a dreamland unlike anything that ever met mortal eye.”

California And The Search For Water

The history of California’s growth is inextricably linked to the search for water. The bustling metropolis of Los Angeles could not have become the city it did without the water which flowed from the Owens Valley hundreds of miles away.

California needed secure, reliable access to drinking water for their burgeoning populations. Not to be outdone by Los Angeles, San Francisco had a greater feat in mind: dam the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park and pipe the water into San Francisco.

“The pressure that Muir and his compatriots generated in 1908 and 1909 did not dissuade the administration from its support of the Hetch Hetchy dam, but this pressure was quite effective in the realm of electoral politics.

-Char Miller, Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism

Congress, confronted with rising public opposition, refused to act on the measure. Hetch Hetchy, for the time being, was safe, and it would not be inundated during Roosevelt’s watch.”

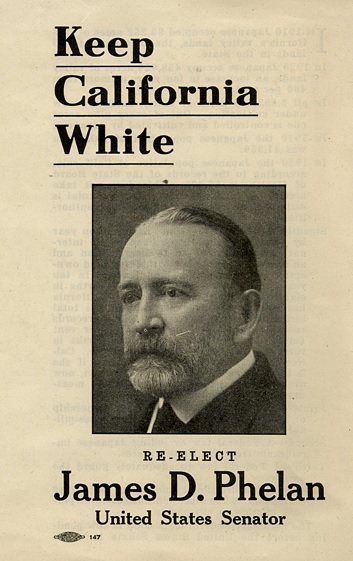

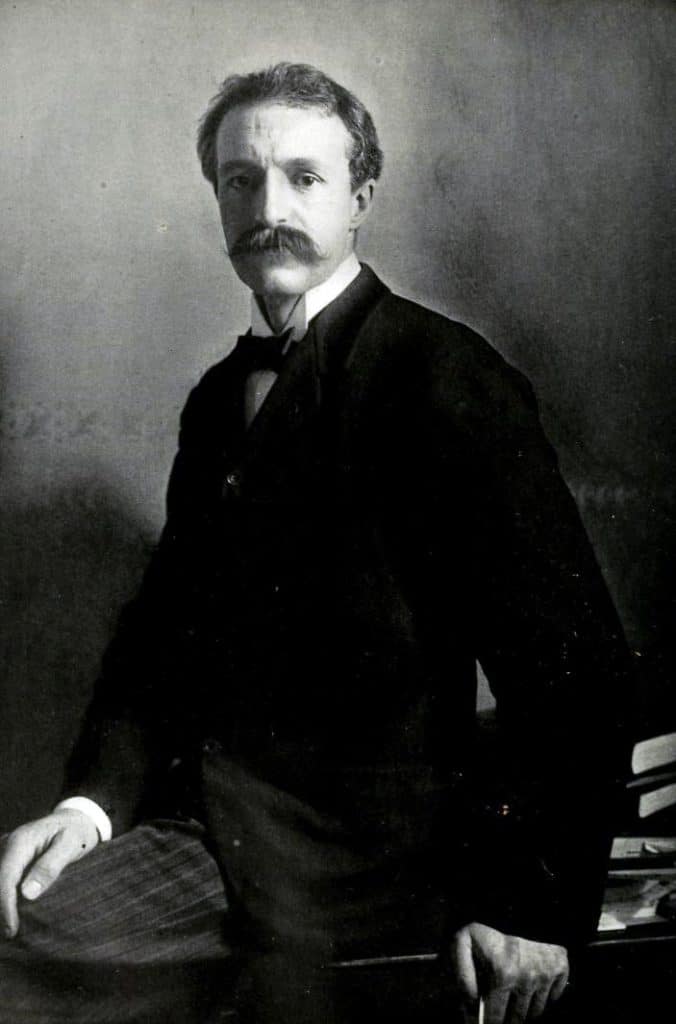

James Phelan & Hetch Hetchy

San Francisco Mayor James Phelan led the fight to build a dam at Hetch Hetchy. As John Clayton writes, “At the height of Progressivism, Phelan and other good-government types believed that the city should administer its own utilities.

To do so, it would either have to buy out the private monopoly at an exorbitant price or outmaneuver or outbid Spring Valley for a potential new reservoir.“

(Source: Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands, John Clayton)

The exploitation of California’s natural resources continued unabated in the years leading up to Hetch Hetchy.

-Robert W. Righter, The Battle Over Hetch Hetchy

Those who presumed to speak for wealth, much of which flowed to San Francisco, believed they were transforming a pioneer land into a settled, civilized one.

And in a larger sense, the waters of California served as the converting agents.

A Fight Over Public Power

The battle for the Hetch Hetchy Valley’s future was not simply preservation versus conservation. Had it been, the Sierra Club’s members would have presented a united front in opposition to its development.

Instead, it was a more complicated battle which pitted public interests against private interests.

The privately owned Spring Valley Water Company had required its customers to pay exorbitant rates for years. Through the manipulation of water, the company also had the power to determine which real estate became valuable and which languished.

Private vs Public Interest

The deciding factor was whether or not the land in question had access to water. Progressive political leaders, of whom Mayor Phelan was one, believed it was time to take this power away from the private interests and turn it over to the people.

On a national stage, Hetch Hetchy became caught in the cross fire between the interests of private utilities ownership and those of municipal ownership.

-Robert W. Righter, The Battle Over Hetch Hetchy

Put another way, if Congress denied the city of San Francisco the Hetch Hetchy Valley, the California Progressive leaders suspected that it would only be a matter of time before the emerging Pacific Gas and Electric Company would grab the area.

If, on the other hand, San Francisco gained control, it would signal in important victory for public power resulting in lower rates for the people.

The Interior Department Waffles on Hetch Hetchy

Secretary of the Interior, Ethan Allen Hitchcock, refused to give San Francisco a permit to build the dam. As the Hetch Hetchy Valley was part of Yosemite National Park, Hitchcock preferred to protect the park’s natural wonders.

By 1908, a different Interior Secretary, James R. Garfield, sided with the utilitarian conservationists and issued a permit for the Hetch Hetchy project.

Garfield was responding to critics who believed that the federal government’s primary responsibility was to use the nation’s public resources for development in the service for the greatest number of people.

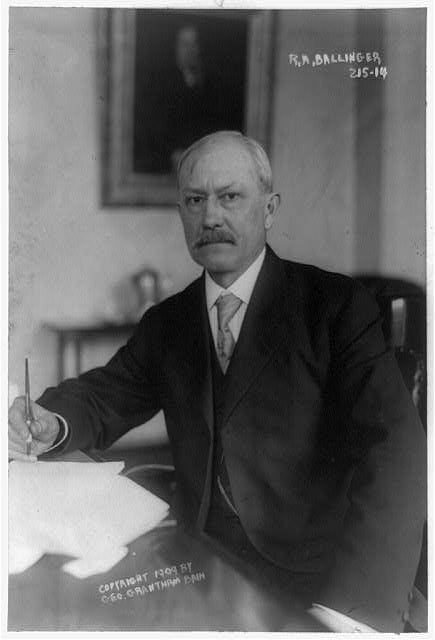

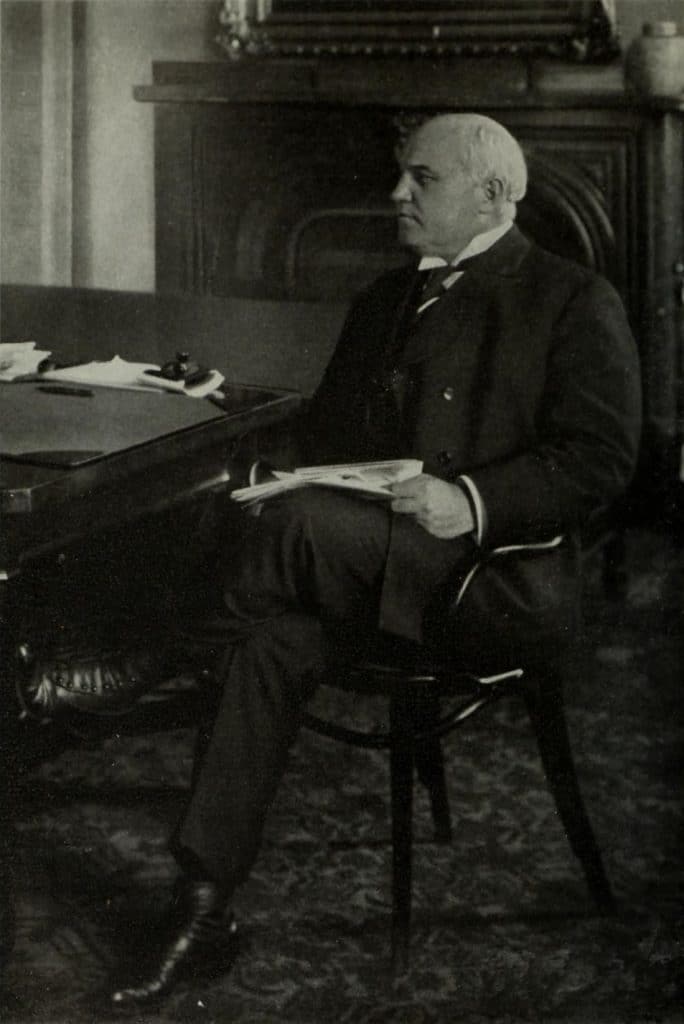

Richard Ballinger & Hetch Hetchy

What one Secretary of the Interior giveth, another taketh away. William Howard Taft became president in 1909. Richard Ballinger was appointed his Interior Secretary.

Garfield had granted San Francisco’s request, but Ballinger ordered the city to show cause as to why Hetch Hetchy should not be deleted from their grant.

Once again, the political pendulum had swung. This time it was in favor those who wanted to preserve the valley for generations yet to come.

The Hetch Hetchy Controversy

John Muir knew that without public support, the Hetch Hetchy Valley would be lost. In an effort to build this support, he published his book The Yosemite in 1912.

Muir famously said, “Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man . . .” For John Muir, it was about preserving a natural wonder which could be enjoyed by generations to come.

The Sanctity of the National Parks

Muir and other defenders of Hetch Hetchy believe the fight revolved around two central issues. First, the beauty of the valley which they felt should not be sacrificed to build a dam. Second, the sanctity of the national parks which they believed should not be violated.

As the battle lines were drawn, the different methods employed by each side in presenting their case spoke to some of their basic assumptions about the nature of the issue.

-The Hetch Hetchy Letters, Jason L. Hanson

San Francisco assumed from the outset that there would not be significant opposition to using the Hetch Hetchy Valley, even if it was in a national park, for the high and noble purpose of providing water to one of the nation’s great and growing metropolises, so their efforts in Washington, DC, were conducted discreetly.

Prominent sponsors of the dam proposal, particularly (by then former) Mayor James Phelan and city engineer Marsdon Manson (and later his successor, Michael O’Shaughnessy), quietly lobbied key figures in the government, trusting that the appeal of municipal water and power would easily win supporters amid the prevailing progressive political climate.

Harriet Monroe & Hetch Hetchy

Next to John Muir, the most vocal defender of the Hetch Hetchy Valley was Harriet Monroe. Monroe was a Chicago poet who joined Muir and others on their 1908 and 1909 outings to the valley. Her poetic descriptions of Hetch hetchy won her the attention of powerful members of Congress.

Monroe went on to lobby members of Congress as the battle moved to Washington D.C. She was a tireless advocate who believed that people needed to be educated in order to do what was best for everyone involved. Like Muir, she felt the beauty of the valley was a national treasure which ought to be preserved.

Gifford Pinchot Takes a Side On Hetch Hetchy

While John Muir led the fight against building the dam, the opposition was supported by Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot was “America’s Forester.” He served as the first head of the United States Forest Service. Pinchot was recognized as a leader of the conservation movement.

He was a firm believer in utilitarian conservation. The question Pinchot always asked was, “What is the greatest good for the greatest number?”

He was famously quoted as saying, “Where conflicting interests must be reconciled, the question shall always be answered from the standpoint of the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run.”

RELATED: Gifford Pinchot: A 2021 Lesson From America’s First Forester

The Greatest Good For The Greatest Number

In his congressional testimony, Pinchot argued in favor of building the dam. He said, “So we come now face to face with the perfectly clean question of what is the best use to which this water that flows out of the Sierras can be put. As we all know, there is no use of water that is higher than the domestic use.”

He went on to say, “We come straight to the question of whether the advantage of leaving this valley in a state of nature is greater than the advantage of using it for the benefit of the city of San Francisco.”

Pinchot argued that applying the principle of the “greatest good for the greatest number,” meant the benefits accrued to the people of San Francisco from having the dam far outweighed leaving the valley in its current state.

A Divided Opposition on Hetch Hetchy

An advantage which Phelan, Pinchot and other supporters of the dam project enjoyed was a divided opposition.

Within the ranks of the Sierra Club, there was a split between those San Francisco members who favored the dam’s municipal use versus those who believed this pristine area should not be tampered with under any circumstances.

(Courtesy of Wikimedia)

The Freeman Report

While opponents of the dam were hard pressed for financial support, the city of San Francisco’s campaign was well financed.

Utilizing its superior resources, the city produced a detailed report which made a compelling case that, far from damaging the beauty of Yosemite, the dam would actually enhance it.

The report cited other dam projects in making the argument that this project would increase tourism.

The Freeman Report artfully depicted reservoirs in Norway, the United Kingdom and the eastern United States showing how nature and public utility worked together to improve their surroundings and provide long-term benefits for everyone.

Woodrow Wilson Appoints Franklin Lane

Once again, the political pendulum would swing. This time, in favor of those who wanted to build the dam. Franklin Lane served as the attorney for the city of San Francisco in 1903.

He had journeyed to Washington to lobby the federal government on behalf of the project. In 1913, Woodrow Wilson appointed Lane his Secretary of the Interior.

Enter Horace Albright

Horace Albright, the second director of the National Park Service, wrote that “Franklin Lane’s appointment to the cabinet was made specifically for the purpose of pushing this [Hetch Hetchy project], the so-called Raker-Pittman Bill.” (Source: The Battle Over Hetch Hetchy, Robert W. Righter)

Albright, along with Stephen Mather, became instrumental players in the creation of a national park system three years after Congress decided the issue of Hetch Hetchy.

RELATED: Meet The Real Life Batman & Robin Of The National Parks

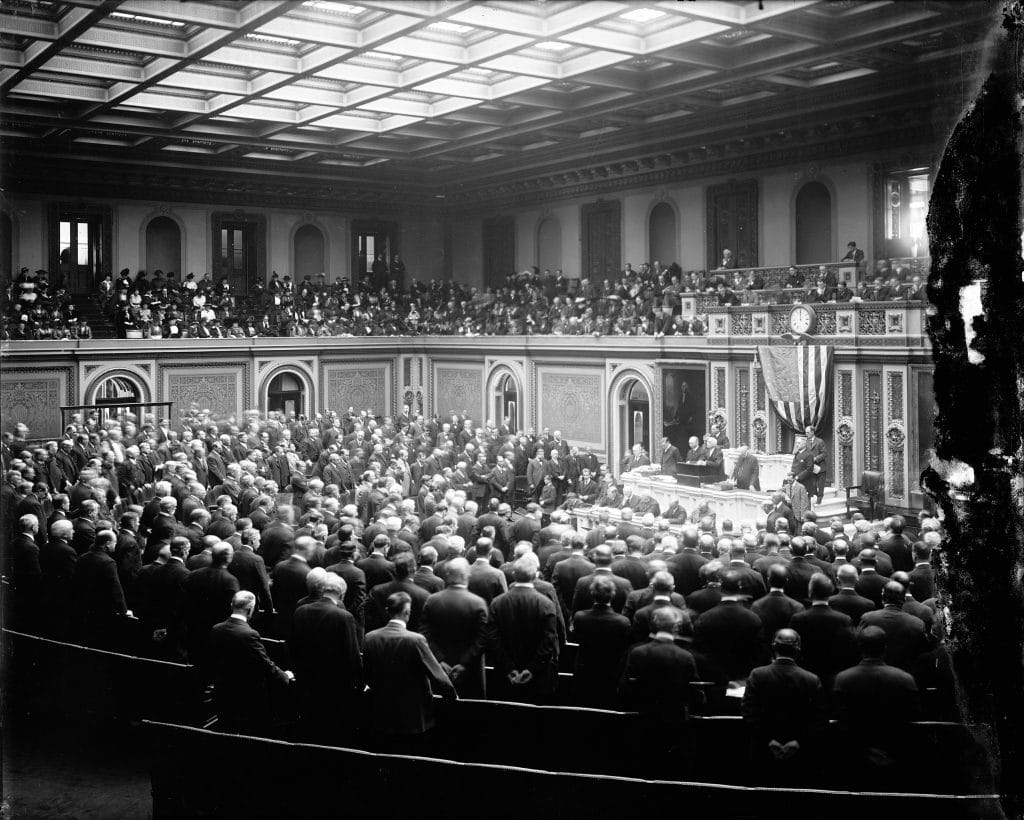

The Raker Bill & Hetch Hetchy

Congress would decide the fate of the Hetchy Hetchy Valley. California Rep. John E. Raker submitted a bill to Congress granting the city of San Francisco the right to dam the Hetchy Hetchy Valley as a reservoir and also provide the city the right of municipalized electricity as well.

The San Francisco Bulletin printed a Dec. 1, 1913, story calling the bill’s opponents “a crowd of

nature lovers and fakers, who are waging a sentimental campaign to preserve the Hetch Hetchy Valley as a public playground, a purpose for which it has never been used.”

On December 19, 1913, Congress passed and President Wilson signed the Raker Act which permitted the building of the O’Shaughnessy Dam and the flooding of the Hetch Hethcy Valley in Yosemite National Park.

The Legacy Of Hetch Hetchy

Environmentalists lost what was the opening battle in a fight to preserve America’s natural wonders. Hetch Hetchy ushered in a new era for the national parks.

It forced elected representatives to consider what a national park designation truly meant and whether or not the land within these parks deserved protection.

The Organic Act

Public disapproval nationwide with the Raker Act helped to bring about the creation of the National Park Service. Within three years, Congress had passed the Organic Act, formally defining the parks and creating a new federal agency, the National Park Service, with a mission:

“…to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

The grassroots organization of environmental activism, established by John Muir and his supporters, became a model for future environmentalists.

Subsequent proposals for development in our national parks have been defeated by citizen activists inspired by calls to remember Hetch Hetchy.

Restore Hetch Hetchy?

In 1987, President Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior, Donald Hodel, proposed that Hetch Hetchy be restored. He was opposed by then Mayor Diane Feinstein who argued that the dam was San Franciscans birthright.

In the 21st century, Ken Brower, son of the renown environmentalist David Brower, wrote a fascinating account of the failed campaign to save Hetch Hetchy and the modern effort to “Reverse an American Mistake,” complete with speculation about how the rebirth of a wild valley might evolve.

Brower’s Hetch Hetchy: Undoing A Great American Mistake, makes a compelling case for restoring the valley to its previous glory.

And today there is even an organization, Restore Hetch Hetchy, which is committed to doing just that.

Visit Hetch Hetchy

Hetch Hetchy Valley is a treasure worth visiting. Located at 3,900 feet, it boasts one of the longest hiking seasons in the park. It’s a a wonderful place to see spring waterfalls and wildflower displays.

High temperatures prevail in summer months, but it’s a small price to pay for the reward of vast wilderness filled with stunning peaks, hidden canyons, and remote lakes.

To Learn More About Hetch Hetchy

- Clayton, John. Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands, Pegasus Books, 2019.

- Miller, Char. Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism, Island Press, 2001.

- Righter, Robert W. The Battle Over Hetch Hetchy: America’s Most Controversial Dam and the Birth of Modern Environmentalism, Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Wolfe, Linnie Marsh. Son of the Wilderness: The Life of John Muir, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1945.

- Worster, Donald. A Passion of Nature: The Life for John Muir, Oxford University Press, 2008.

Helpful Related Articles

Things to Do in Yosemite: 20 Epic Things to Do in Yosemite National Park

Best Hikes in Yosemite: 20 Best Hikes in Yosemite National Park

Yosemite Facts: 10 Shocking Yosemite National Park Facts

Hetch Hetchy: Hetch Hetchy – The Epic Enviro Battle That Changed America

Things to Do Sequoia: 15 Amazing Things to Do in Sequoia National Park

Redwood National Park: Redwood National Park Ultimate Guide

Things to Do Redwood National Park: 15 EPIC Things to Do in Redwood National Park

Death Valley National Park Guide: Death Valley National Park Ultimate Guide

Things to Do Death Valley: 18 EPIC Things to Do in Death Valley National Park

Joshua Tree Guide: Joshua Tree National Park Ultimate Guide

Best Hikes Joshua Tree: 15 Epic Hikes in Joshua Tree National Park

Things to Do Pinnacles National Park: 10 Epic Things to Do in Pinnacles National Park

Redwoods Near San Francisco: 15 BEST Places to See Redwoods Near San Francisco

Los Angeles National Parks: 7 Epic National Parks Near Los Angeles

San Francisco National Parks: 8 BEST National Parks Near San Francisco

San Diego National Parks: 6 AMAZING National Parks Near San Diego

Sequoia Facts: 10 GIANT Sequoia Tree & National Park Facts

Channel Islands Facts: 10 Amazing Channel Islands National Park Facts

West Coast Parks: 20 BEST West Coast National Parks Ranked by Experts

This is interesting from an ideological perspective. The battle for Hetch Hetchy wasn’t just conservationists vs preservationists. It also was an early battle of conservatives vs progressives.

Richard Ballinger was a conservative who was one of the main characters who was responsible for the progressive-conservative split in the GOP in 1912 (leading to the creation of the Bull Moose party), which is the factor that determined the GOP would be on the right side of the political spectrum (and therefore ensuring the Democrats would be on the left side of the spectrum).

Indeed, the battle over Hetch Hetchy may have been a little-known contributor to the permanent alignment of American politics – it was the tension between Ballinger and Pinchot that set in motion the events that lead to the split mentioned above.

I will agree to take down Hetch Hetchy, when we first replace it with a bigger new reservoir such as a bigger taller Yosemite Valley dam at El Capitan. You could then scuba ElCapitan down to the valley floor.